It was a random day in August when a trade paperback copy of Lonesome Dove showed up in the mail from Simon & Schuster. It didn’t come with a press release or a note, and I’m still not sure who sent it to me (I’ve asked a few S&S publicists and it remains a mystery!), but I took it as a sign. I had just turned around final edits for my book, and I was ready for a project. The Pulitzer Prize-winning 1985 epic is an all-time favorite novel of some of my favorite people and I’ve been hearing raves about it forever, and so I decided to go in.

Article continues after advertisement

The 2010 edition of the book features a quote from USA Today on the back cover that clinched the deal: “If you only read one western novel in your life, read Lonesome Dove.” The 2010 edition also comes with an introduction by the author, Larry McMurty, who died in 2021. It’s a lovely piece of writing but in the space of two pages he sets up and then immediately spoils—mildly but still!—the following 858 pages of the book (why do intros do this?). Still, I went on.

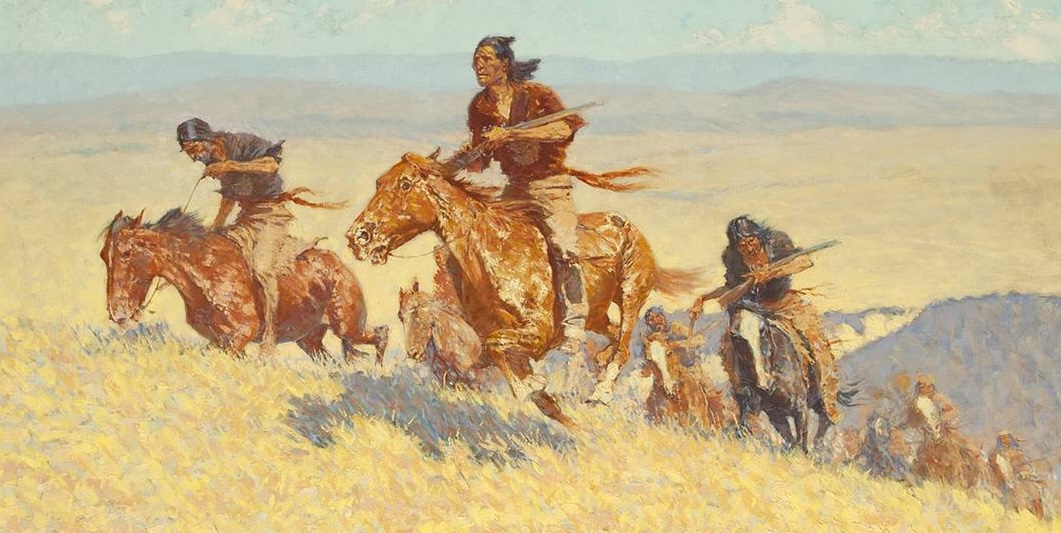

I confess: I very much appreciated Lonesome Dove, and that’s about it. It wasn’t the life-changing read I had been led to expect. It was not, as they say in the book marketing biz, “unputdownable.” It is a beautifully constructed novel that meanders through a variety of different points of view and landscapes in post-Civil War America. We come to know the entire crew of cowboys who face almost Biblical obstacles while driving cattle from Texas to Montana, plagued by heat and hail and grasshoppers and snakes and snow. There is a vastness to the unsettled (by white people, anyway) land they travel through, the kind that is meant to signify endless opportunity in the Western genre and in American literature itself, but so often, in this book, just feels like loneliness and emptiness (this is a compliment).

I don’t want to think that I didn’t love Lonesome Dove because I couldn’t see past the problematic parts.

So why didn’t I love Lonesome Dove? It may be that it was simply overhyped, that my expectations were too high. Here’s Kirkus: “This is a masterly novel. It will appeal to all lovers of fiction of the first order.” Once we start getting into Great American Novel territory and all that it implies, I’m likely to want to back away slowly, but for the most part I’m not contrary by reflex. I like to like the things that people I admire enjoy.

I don’t want to think that I didn’t love Lonesome Dove because I couldn’t see past the problematic parts. Of course any traditional Western is going to be chock full of bad politics, with its ragtag gang of main characters encountering and othering Mexicans and Indians (sic) and whores (sic) as they make their way north. I very much believe that McMurtry wasn’t trying to brush past all of the less savory actions of his characters. Nor were all of his cowboy characters dripping with machismo. We get to see vulnerability in just about every member of the crew except for the leader of the drive, Captain Woodrow F. Call, who is notoriously unable and unwilling to feel feelings.

Why didn’t I love Lonesome Dove? I remember my mother telling me about how when she saw a classic horror movie on its initial release, she was not able to sleep for nights afterward or think much about anything else. By the time I saw it, Psycho didn’t rattle me in the same way simply because its plot and the style in which it was shot, so revolutionary at the time, felt ordinary to me. I’d never read Lonesome Dove before now, or watched the miniseries starring Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones, but I’m sure it seeped its way into popular culture and into my brain all the same. I came to it already familiar.

And then I realized that some of my favorite recent books have been subversions of that typical Western narrative, novels (and a story) that mix all of the hallmarks of the genre with more modern ideas and interpretations. From Annie Proulx’s short story “Brokeback Mountain,” for which McMurtry co-wrote the movie screenplay, to Hernán Diaz’s debut novel that is being republished next week by Riverhead, to the comic masterpiece that is Patrick deWitt’s The Sisters Brothers, it’s been lovely to see how the standard of the Western genre has given way to more inventive works. Even in the past few years the genre has been entirely reinvigorated by novels like Lone Women by Victor LaValle, How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang, The Thousand Crimes of Ming Su by Tom Lin, Inland by Tea Obreht, and The Best Bad Things by Katrina Carrasco.

The Western has been revived and I’m here for it. I’m glad to have made my way through one of the genre’s foundational texts, but so excited to read the more subversive texts that follow.