Artists with developmental disabilities have produced a rich archive of community-driven art since the founding of Creative Growth, a pioneering center dedicated to such creators in Oakland, California, in 1974. Half a century later, the Museum of Modern Art is dedicating a solo exhibition to an artist from these studios for the first time. Marlon Mullen, who has worked for decades at NIAD Art Center in Richmond, California, transmutes the signifiers found on the covers of art magazines and books into paintings that pulse with his singular vision.

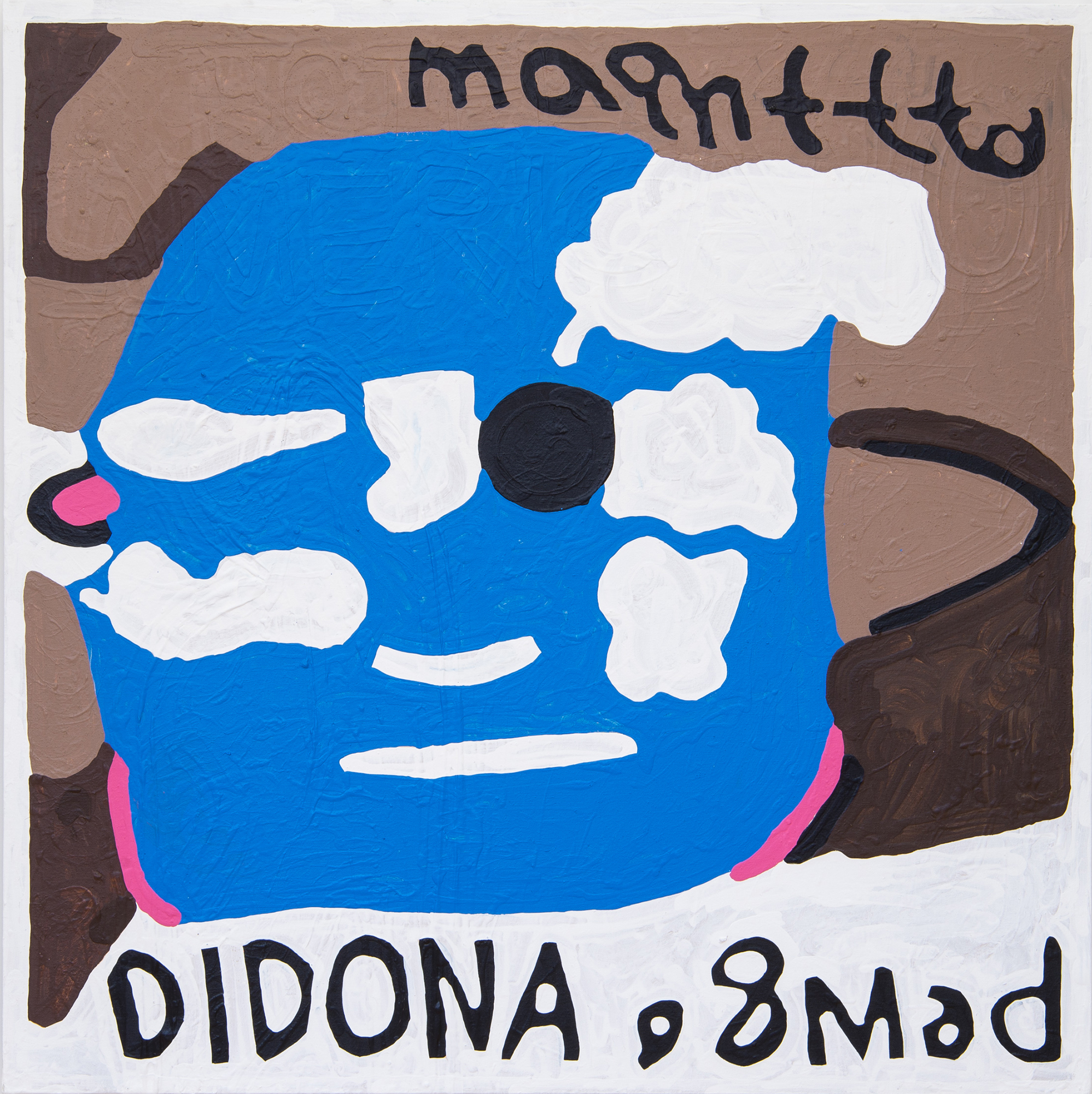

Recognizing Mullen’s referents is key to his paintings’ initial pull — the Artforum logo, for instance, or Warhol’s Marilyn, whose expression is playfully exaggerated here. But the artist’s thick paint application adds texture missing from the largely two-dimensional referents, lending his works a more human quality. Mullen, for instance, replaces a 2002 Art in America cover with a two-by-three grid of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s black-and-white photographs of rigid framework houses with a network of connected organic lines. In doing so, Mullen eviscerates the logic of the original artworks, as well as that of the covers on which they are reproduced via misspellings and the rearranging of letters and layouts. Germany becomes “Grmany”; an “R” and a “T” fuse into a shape reminiscent of the Pi symbol. White borders that neatly separated the Becher houses disappear as Mullen’s rendition smushes them together.

Each painting sees Mullen reacting in real-time to the forms he’s producing, revealing the details that interested him in the act of making. Mullen’s take on Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” (1889), drawn from the cover of a MoMA publication, is marked by more emphatic brushstrokes than the original and the use of flat, long applications of paint to extract specific colors from the dancing sky. While certain works feature a staccato of black lines against a white rectangle in the corner — an exaggerated rendering of a barcode — this same element is absent in other paintings. In the above work, the artist even omits MoMA’s logo in the corner of his reference, denying the source’s intention. Yet these images can never wholly be divorced from their inspirations, forcing us to ponder Mullen’s perspective in dialogue with art history.

Despite the strength of the exhibition’s installation, I sense a curatorial hesitancy to make clear statements on the artist’s work, ironically distancing him from the interpretive rigor afforded other artists. While gallery didactics provide essential context, they never probe how museum collections and the United States writ large marginalize those with disabilities, or address how disability generates creativity. This might reflect the lack of expertise in critical disability theory in museum curatorial departments, a gap that could be closed by inviting external curators and scholars. Yet Mullen’s work rises above these concerns in their sincerity and originality — an argument in itself for a more capacious consideration of disability and art.

Projects: Marlon Mullen continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown Manhattan) through April 20.