Bill Schutt, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History and former biology professor, has just put out his third book: Bite: An Incisive History of Teeth, from Hagfish to Humans. (His two previous titles were on the heart and on cannibalism.) Schutt’s interest in teeth largely stems from his desire to have insights into evolutionary “vertebrate innovation.” The tooth is a vital the way in, Schutt argues—above even brain evolution.

Article continues after advertisement

“The appearance of teeth, around 500 million years ago,” he writes, “enabled myriad forms of vertebrates to obtain and process food in pretty much every conceivable environment—from sun-torched deserts to oceans and rainforest with thousands of species of animals and plants.”

In Bite, Schutt of course discusses teeth in a variety of animals, including vampire bats and horses, as well as a variety of kinds of tooth, from incisors to tusks to fangs. Whether it’s a frill of odontodes, teeth that live in pharyngeal jaws, or ancient mandibular tusks, all are worthy of investigation here. A chapter in the human section entitled “Tooth Worms” was, unsurprisingly, something I had to steel myself to turn to (rest easy: people attributed toothaches and cavities to worms for centuries before we learned the truth).

All the above illustrate how Bite is chock full of wild facts. Par example: an early proponent of tooth transplant, John Hunter, tried to prove its feasibility by grafting a tooth into a rooster comb? (Tooth transplantation isn’t possible because the minute arteries in the jaw and tooth wouldn’t line up, to start.) In its starred review of Bite, Kirkus Review calls it “A fascinating romp through evolutionary history.”

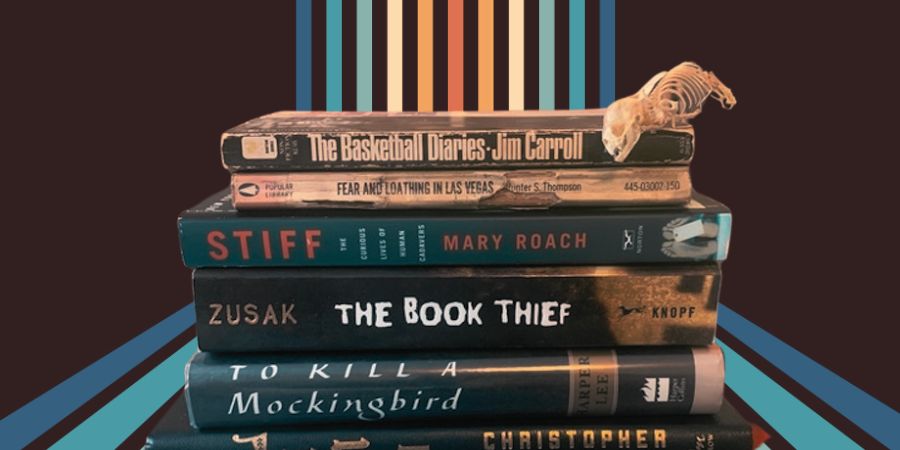

Schutt says of his to-read pile:

The books in this stack are not only some of my all-time favorite books, but they were also influential in my search to become the best writer I can be. Some served to illustrate that even complex subjects can be tackled in entertaining and humorous ways. Others inspired me to care about using words to paint a clear picture of any topic or scene—instilling in me the importance of getting every line just right. Finally, the vampire bat skeleton is there to remind me how the wonderful experiences I’ve had as a scientist and writer all began.

*

Jim Carroll, The Basketball Diaries

Jim Carroll is largely known as a poet and punk rocker who grew up in New York who got into heroin depressingly young. Prior to that, Carroll had earned a scholarship to an elite private high school in New York, where he was a basketball star. In the 1960s, he began using heroin at thirteen and he did sex work in Midtown East to pay for the drug. He also wrote poetry at St. Mark’s Poetry Project, played basketball in the National All-Star Game.

The Basketball Diaries is based on Carroll’s diaries from this time. He managed, somehow, to keep all these plates spinning long enough to graduate, attend a bit of college, live with Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe (dating the former), become a musician, and a million other wild adventures.

Smith once said of Carroll:

He lives a disgusting life. Sometimes you have to pull him out of the gutter. He’s been in prison. He’s a total fuck-up. But what great poet wasn’t? It kills me that at twenty-three Jim Carroll wrote all his best poems—the same year of his life as Rimbaud did. He had the same intellectual quality and bravado as Rimbaud.

You can read some of The Basketball Diaries over at The Paris Review.

Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream

One of the things I love about writing this column is learning new things about literature I thought I already had a sense of. But here I am, learning Fear and Loathing has a subtitle! (Granted, much of my knowledge of the book is from this brief moment in The Simpsons.)

I’m also glad to learn more about Oscar Zeta Acosta, the Dr. Gonzo to Thompson’s Raoul Duke in the book. Acosta was an activist attorney involved in the Chicano Movement. Thompson wanted to interview Acosta extensively about himself, the death of Mexican American journalist Rubén Salazar at the hands of a sheriff’s deputy, and the ways in which police were vicious to the LA Latinx community.

But the two men found racial tensions in Los Angeles made public conversations between people of their two races difficult. On the pretense of a Sports Illustrated gig, the two went to Vegas, twice, and apparently got into nonstop chemical shenanigans (but apparently spoke enough for Thompson to write “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” about the topics the two needed to discuss).

Mary Roach, Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers

In its starred review of Stiff, Kirkus Review writes,

From the opening chapter, in which forty severed human heads are prepped for a plastic-surgery seminar, to the final one, in which whole bodies are plastinated with liquid polymers for a museum exhibit, [Roach] proves herself a keen observer and unflagging questioner…While Roach provides a vivid picture of the macabre activities she witnesses, it’s her offbeat musings, admissions, and reactions that give such life to her tales of the dead. She also provides history, mostly focusing on body-snatchers and the anatomists who used their services. Roach delights in imparting odd information, such as the fact that eighteenth-century students at certain Scottish medical schools could pay their tuition in corpses rather than cash, and when the curious facts unearthed by her research don’t fit neatly into her narrative, she slips them into droll footnotes.

Markus Zusak, The Book Thief

The Book Thief, initially intended for younger readers, follows a teenaged girl in Germany during WWII. Powerfully, the book is narrated by Death. This fifth novel by the Australian writer who had previously done pretty well for himself, has sold *seventeen million copies* and been translated into dozens of languages. I mean success and visibility is great and all, but whew! For some context, this is five million more than all three of Rupi Kaur’s books combined.

Sara Grochowski interviewed Zusak in Publishers Weekly and asked how The Book Thief impacted his next book. He states,

When a book does so much better than you’ve anticipated, so much good stuff comes with it. You get to visit countries you’ve never been to before and do things you’ve never dreamed possible. But, when the doors open that wide, a bit of darkness comes through, too….You’re always having to ask yourself, how much do I want this? It wasn’t a struggle to put food on the table and that sort of thing, so writing became more of a quest of will. Eventually, you just do the work, you let go, and you become yourself again. And you realize, my job is just to make this book how it needs to be.

Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

I had long-heard the (rude) rumors that Lee didn’t write To Kill a Mockingbird, but that her bestie Truman Capote did. What I did *not* know was that scholars ostensibly cracked the code on this.

Employing stylometry, Michał Choiński studied a series of Southern writers of Lee and Capote’s era to locate “authorial fingerprints.” In an article for LSU Press, Choiński includes several images and graphs of these findings, and describes the clear authorial traces of Lee and Tay Hohoff (her editor) in the book.

He writes,

While this mixture is quite a natural effect of the women’s two years of collaboration, the presence of Truman Capote’s signal (in red) in the opening chapters of To Kill a Mockingbird is somewhat surprising. Could this residue be the outcome of their shared narrative of their upbringing in Monroeville, Alabama? Did Capote indeed help his younger colleague a bit with the very opening sections of the book? This stylometric study encourages us to give more thought to Capote’s role in the early stages of Lee’s writing endeavor.

Christopher Moore, Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Moore leans into the phenomenon of Christian apocryphal texts regarding Jesus and his life, in this case told from the perspective “Levi bar Alphaeus” aka Biff. The jacket copy for this hilariously subtitled book reads:

Everyone knows about the immaculate conception and the crucifixion. But what happened to Jesus between the manger and the Sermon on the Mount? In this hilarious and bold novel, the acclaimed Christopher Moore shares the greatest story never told: the life of Christ as seen by his boyhood pal, Biff. Just what was Jesus doing during the many years that have gone unrecorded in the Bible? Biff was there at his side, and now after two thousand years, he shares those good, bad, ugly, and miraculous times. Screamingly funny, audaciously fresh, Lamb rivals the best of Tom Robbins and Carl Hiaasen, and is sure to please this gifted writer’s fans and win him legions more.

Stephen Jay Gould, Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History

“One fine day a half-billion years ago, an underwater mud slide (or some other catastrophe) buried a mob of strange creatures in what has now become a slab of exposed rock known as the Burgess Shale, high up in western Canada’s Yoho National Park. They are certainly the weirdest animal fossils ever found, and they could easily be—as Stephen Jay Gould argues in his extraordinary book ‘Wonderful Life’—the most important,” writes James Gleick in his 1989 review for the New York Times.

When the movies try to design alien life forms, they unwittingly reveal our lack of imagination about the different paths life can take. They tend to fall back on a standard body plan – with crusty or gnarly skin, perhaps, but basically the same old animal. The Burgess Shale provides a heady antidote to lack of imagination. This one slab of rock, now abetted by more recent fossil discoveries, reveals more disparate basic body plans, Mr. Gould says, than all the creatures now swimming or floating in the earth’s oceans. “Little taller than a man, and not so long as a city block!” he writes of the site. “How could such richness accumulate in such a tiny space?”

Edward O. Wilson, Naturalist

Josh Getlin writes for the Los Angeles Times in a 1994 review that Wilson’s Naturalist is

an eye-opening memoir of intellectual growth, showing how he evolved from a reclusive boy hooked on bugs into a scientist who’s duked it out on the world stage. For those who shun science writing, Wilson’s vivid prose can be a revelation. He’s long had the knack of making complex biology seem relevant to a general audience, and students rate him one of Harvard’s top lecturers. He displays the same skills in his latest book….Academic warfare fills the book, and Wilson loves to filter it through a biological lens. Look for the roots of human behavior in the past, he says, whether you go back fifty years or fifty million years. His boyhood fights and faculty clashes may seem anecdotal, but aren’t we really talking about Paleolithic man, male initiation rites and tribal warfare? “I can’t help but look at the world this way, because the past always repeats itself.”