In the summer of 1906, Paul Nash left school. He was sixteen years old and feeling bemused. He didn’t want to follow in the family tradition and join the navy, and no one was taking him seriously about his desire to be an artist. So he took the train up to London.

Article continues after advertisement

He often did so, because the city was a scary and exciting place. Over in Paris that summer there were anarchist bombings. In imperial London, things seemed more secure.

But within an hour of leaving his comfortable home in Buckinghamshire, the teenager could be strolling down Piccadilly, following in Oscar Wilde’s steps, to a new sort of space. It was a secret street, Nash said, and the Carfax was the most distinguished and exclusive gallery in London.

It was always afternoon there, someone said, and there were always tall, vague, well-dressed men talking about unknown poets. It had the air of a forbidden place, like a nightclub, not least because it was managed by Robert Ross, Wilde’s devoted friend.

So devoted that when Oscar’s surprisingly unrotten corpse, his hair and his beard having continued to grow after death like a saint, was exhumed in Paris to be taken to Père-Lachaise, a better address to be seen dead in, Ross stopped the sextons lifting it with their spades and stepped into the grave to raise up his long-dead lover in his own arms.

Wilde had hardly died in 1901. He lived on like an impeccably dressed wraith, still disturbing the course of society with his wit and willfulness. Ross’s acquisition of the Carfax was financed by his loyal mother, Augusta Elizabeth Ross, who, when Wilde was arrested, had paid £500 towards the cost of his defense on the condition that her son left the country to avoid arrest himself.

He never went. Wildean people lingered from the nineties, when nobody was very old, as another of Oscar’s lovers said. They hung around as a faint scent, waiting for what came next.

Ross lived just across Piccadilly from the Carfax, at 40 Half Moon Street, another hidden address. It was there in 1918, the last year of his life, that he would play host to the young war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, both of whom took rooms in that establishment for single gentlemen of a certain kind.

He lived on like an impeccably dressed wraith, still disturbing the course of society with his wit and willfulness.

Ross had his salon painted gold in protest against the conflict; like Owen, he kept photographs of mutilated soldiers in his pocket to show to anyone who supported the war, like some terrible tarot card. That same year, Nash met Ross socially; perhaps he was entertained in that golden room with its Turkish cigarettes and sugared almonds. But he was certainly a visitor to the Carfax long before that.

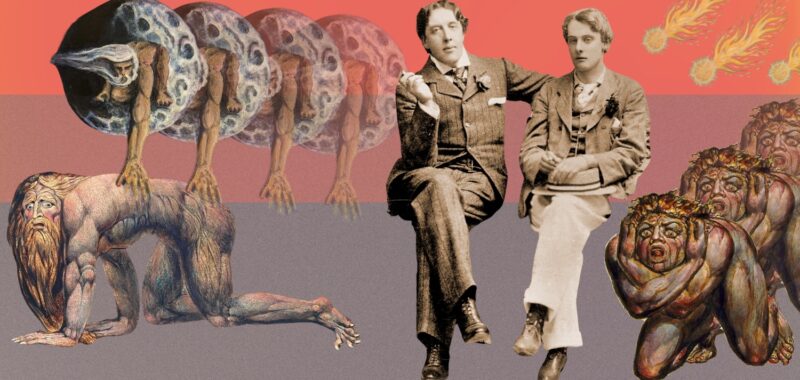

In June 1906 the gallery held a great exhibition of work by William Blake, who, as Ross told the readers of the Burlington Magazine, constituted no link in English painting. Unlike other important artists such as Turner or Constable, Blake did not change the character of art, and for this reason he has been overlooked.

With delicious Wildean ambiguity, drawing on his Turkish cigarette, Ross declared Blake to be an exquisite accident.

But this was no accident. None of it was. There were good reasons for the cult that had grown up around Blake. The cofounder of the Carfax, the artist William Rothenstein, another friend of Wilde, had a particular connection to Blake via Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites, who had seen in the wildness of Blake’s work the seeds of their own brotherhood.

Yet for all their efforts—or perhaps, because of them—Blake remained an outsider, a freak; and now, to mark his strangeness, accidental or otherwise, the Carfax assembled the most extensive and comprehensive exhibition of his work to date, as Ross boasted.

It was a sensation, a freak show, and if Paul Nash was waiting for someone or something to transform him, nothing could fit the bill better than the announcement slipped almost surreptitiously into the pages of The Times. It was enough to make you hold your breath. The circus had come to town.

Not everyone was convinced; that was the point. The paper’s critic was distinctly equivocal. Blake was too weird, too little sane, to excite a very deep interest, he declared. But he also acknowledged that while the wild, imaginative remoteness and the formlessness of Blake’s work could disconcert, he was the only artist of his time who could paint spiritual visions (angels and the like) without making them ridiculous.

Another reviewer of these angels and devils called the pictures performances, as if they were works in progress, still going on. Which they were, of course; that was the point too. A third reviewer insisted that to call the artist important would be absurd, but had to admit that there was now a persistent and insistent cult of Blake which could not be denied.

A crack in the sky opened up and a hand reached down. It was a great connection for a young artist to make: from Blake’s obscurity to a new age that claimed him as one of their own. Blake’s stars aligned in a way they had never done while he was alive.

It was all down to fate. That his works survived at all owed much to his loyal patron, Thomas Butts, who had bought pictures almost weekly from Blake and whose descendants had miraculously preserved them in their private gallery. And it was there that they were rediscovered by another young man who would become the instrument of Blake’s resurrection, installing him as a kind of prophet for modern art.

*

In the summer of 1894, John Singer Sargent stood in his studio in Chelsea, its huge window looking down to the river at the end of the street. Inscribed in terracotta plaques over Sargent’s doorway were two quotations: To Thine Own Self Be True and The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Fear Itself.

Oscar Wilde, who lived at the other end of the street, had only to peer over his balcony to see what was going on. Who was coming and who was going. It was all a performance. Inside Sargent’s studio, one of the great set pieces of the period was under way: a picture that would become something more than merely the portrait of a wealthy young man. Something mysterious and grand.

W. Graham Robertson was already renowned as the first of Wilde’s favorites to wear a green carnation. Now, in the heat of summer, Sargent was painting him as a very thin boy in a very tight coat, as the model himself would recall.

He posed there for hours, the light falling on his face; his jade-topped cane in one hand, the other on his hip; his boon companion, Mouton, a lamb-like poodle from Biarritz, lay at his feet. At the beginning of every sitting, Mouton bit the painter. He has bitten me now, Sargent said, so we can go ahead.

For the artist, the whole composition revolved round the garment and its black velvet collar. So he made Robertson take off most of his clothes underneath; not so much as to keep him cool as to make him look even thinner, all the more like the immortal aesthete they were creating; all the more like a relic of the future past.

In the text, which he entrusted to Ross for publication, Wilde resorted, in his despair, to quoting William Blake.

Sargent knew his power. His portraits swirl with glamour and poise; his evocation of children lighting lanterns in the violet twilight, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, painted between games of tennis, makes even time look like a theatre set.

All of his paintings were events. They drew a select crowd. His friend and fellow American, Henry James, came in to see Robertson’s portrait, several times; perhaps he was taking notes. Sarah Bernhardt peered at it on tiptoe, her head thrown back. The whole thing might have been a drama written by Wilde over the road. Everyone hiding in plain sight. Life imitating art. The alluring young man, an artist himself, ready to play his part.

When Sargent asked him why he hadn’t painted a self-portrait, Robertson replied, Because I am not my style.

What do you allow your friends to call you? Wilde asked him. W? or Graham? I like my friends to call me Oscar.

Their friendship flourished in words and gestures. Oscar thanked him for his dancing and told him not to read his Picture of Dorian Gray. You can see why: the book opens with an artist painting the portrait of a young man who is doomed by his extraordinary personal beauty. But did Robertson obey? He had the look of a faun in Mayfair; those might be goat’s legs under his West End coat.

You are made for olive-groves, Wilde told him, and for meadows starred with white narcissi. I tried to invent a fairy tale for you to illustrate. I kept looking at the moon.

And when Robertson sent his drawings, Wilde replied, The star-child is lovely: it is clear you have seen him.

But there’s already a sadness in Robertson’s eyes. He had shared Mouton with Walter Hiley, his first friend. They’d been at school together. Hiley had joined the army. On leave, he came to stay with the Robertsons in Mayfair, suddenly took ill and died, aged twenty-one.

A year later Robertson met Oscar and everything changed again. He tried to forget his first friend and the promises they made. Sargent’s picture was a portrait in a mourning coat. It was also a dangerous image. The artist in Wilde’s book never tells his friends’ names to anyone. It is like surrendering a part of them, he says.

After Wilde was imprisoned as convict c.3.3., as though they’d tried to destroy his identity, he wrote to Alfred Douglas from Reading Gaol in an extended letter that became known as De Profundis and which would address his sense of betrayal. In the text, which he entrusted to Ross for publication, Wilde resorted, in his despair, to quoting William Blake.

Where others, says Blake, see but the Dawn coming over the hill, I see the sons of God shouting for joy.

But Oscar knew it was a forlorn hope, as he acknowledged in the next line: “What lies before me is my past.”

It is hard now to comprehend the hatred Wilde faced, dead or alive. The news traveled as far as Nebraska, where Willa Cather declared, Civilization shudders at his name. My mother, born in 1921, understood he was a wicked man, but no one would tell her why. Even Robertson’s own friend, Kerrison Preston, writing in 1953, spoke of the sinister evil inherent in Wilde as the older man in the relationship.

Passers-by in this drive-by shooting casually described Wilde after the fact (we knew it all along, but were too well bred to say) as a plump, pasty, flabby, round-faced, preposterously-garbed man at their family wedding, delivering an outrageously flattering speech which produced a slight feeling of nausea. They were so afraid. They had no name for what he was.

When we see people in old photographs we wonder where in time they were. Robertson was immortal in Wildean guises, changing shape. Dancing in white tights and flipperty-flopperty hat; in velvet jacket, waistcoat and breeches, doubly exposured, in two places at once like Jekyll and Hyde or a little ghost.

______________________________

William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love by Philip Hoare is available via Pegasus.