From essays to interviews, excerpts to blog posts, reading lists to poems, we publish a lot of good stuff at Lit Hub, if we do say so ourselves. And while we are proud of all of the pieces we’ve shared in 2024, we all have our personal favorites. Below are a few of the Lit Hub features the staff loved best from this past year.

In Search of the Rarest Book in American Literature: Edgar Allan Poe’s Tamerlane

by Bradford Morrow

Bradford Morrow’s wonderful essay is an investigation and celebration: in anticipation of the auction of one of only twelve remaining copies of Edgar Allan Poe’s debut collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, Morrow unpacks the history of the book and profiles one of the book’s collectors. As his own novel, The Forger’s Daughter, focuses on a complex scheme to counterfeit a thirteenth Tamerlane, here he is both a researcher and a fan, making the piece not only incredibly informative but a fun, suspenseful read. (He thankfully followed up with the results of the auction, too, which you can read here). –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Envy, Obsession, and Instagram: On My Mental Breakdown at an Esteemed Writing Conference

by Brittany Ackerman

Envy is a curiously taboo topic for writers, particularly published writers. It’s also a topic with which all writers (and humans) are well acquainted. Brittany Ackerman beautifully documents that universal scourge with urgency and pathos, and, most importantly, humor. This piece is essential reading for anyone who has ever scrolled Instagram in the dark feeling like a nobody (again: humans). –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

The Joys and Fears of Trans Motherhood

by Gabrielle Bellot

This essay was originally published in August and its concerns resonate even deeper in a post-election reality: How do you live in a country that weaponizes your identity, and that seeks to take away your basic human rights at every turn? In navigating the painful territory of prospective trans motherhood in America, Gabrielle Bellot has ended up writing a beautiful meditation on what it means for anyone to be a mother, metabolizing—with customary grace and insight—all the hopes, fears, and cares that role entails:

“No one should be shamed for choosing childlessness, and families should be able to have any structure the adults consent to. Yet in a country so fanatically obsessed with children, it’s tellingly difficult, if not financially implausible, for certain families—ones who look like my wife and me—to bring another of those kids into the world, especially if you merely happen to live in the wrong part of the county.”

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Intifada: On Being an Arabic Literature Professor in a Time of Genocide

by Huda Fakhreddine

I still shake a little bit when I think about the power of this essay. In something like 3500 words, Huda Fakhreddine pulls off a magic hat trick: she roots us in the present censorship of the Palestinian people on American college campuses, she shares a staggering slice of autobiography about her own experience of Israeli occupation and violence, and she helps clearly define—for an audience that perhaps hadn’t had a clear definition for any number of reasons—the expansive and necessary breadth of the word ‘intifada.’ It is an excoriation of the American reluctance to face difficult things, as exemplified by the institutions that are meant to be teaching our young people to expand their minds but are instead shrinking the window of tolerance in a panic. It is, to put it bluntly, required reading. –Drew Broussard, Podcasts Editor

As a Writer, You Can Never Collect Too Many Endings

by Steve Edwards

I love a craft essay that leans heavily on the essay side of things, that has the feeling of setting out to explore without a map. Steve Edwards’ piece on collecting endings is so gently told that it feels like strolling with a friend, and his emphasis on the quiet, writerly practice of observing is empathetic. It’s not an impulse to control, but a practice built around trying to understand and be more deeply in the world. It’s writing advice that isn’t mercenary, or efficiency-minded. It’s practical in a way that’s inspiring—craft discussions can march too rigidly into the overly prescriptive, but I love Steve’s embrace of the unknown and of possibility as a way of being and writing. –James Folta, Staff Writer

Generation Franchise: Why Writers Are Forced to Become Brands (and Why That’s Bad)

by Jess Row

As the social media paradigm of the 2010s splinters into an ideological multiverse of echo-chamber shit-posting I, for one, am eager to read the obituaries. And though not exactly that, Jess Row’s ornery analysis of “the writer as digital brand” is a great place to start. To wit:

“Over on the (actual) literary Internet, it’s been nothing but frustration, disillusionment, and disengagement for years—first with waves of writers exiting Facebook, then the-platform-formerly-known-as-Twitter, and finally, in plenty of cases, social media altogether. Some writers, it’s true, have tried migrating to newer platforms (Bluesky, Mastodon, Threads) or reluctantly returned to the old ones with a mixture of disgust, hand-wringing, and resignation. But the vibes are off.”

–JD

The 167 Best Book Covers of 2024

This is my favorite part of my job every year—asking a whole host of great book cover designers (whose work is, in my opinion, not celebrated and discussed enough) about their own favorite book covers of the year. At the risk of twitching the veil, putting it together is a huge, painful, spreadsheet-heavy endeavor, but it’s always worth it. The result this year was a whopping 167 different book covers, from multiple countries, many of which I’d never seen before. Give me all the good design—my mood simply requires it this time of year. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

The Social Media Project Humanizing Palestinians Killed by Israel, One Person at a Time

by Steven Thrasher

Every one of Steven Thrasher’s blazing 2024 columns should be required reading, but I want to highlight his March interview with Rozan, the founder and lead writer of Martyrs of Gaza, a social media project that memorializes Gazans killed during Israel’s ongoing assault on the besieged enclave: “As the gruesome deaths of Palestinians by hunger or drones fill our social media feeds but go largely unreported by mainstream media, The Martyrs of Gaza project is a needed antidote to the common way journalism dehumanizes the people actually being killed in the Gaza genocide by commission of omission.” –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

What the New York Times Missed: 71 More of the Best Books of the 21st Century

When the New York Times announced its “100 Best Books of the 21st Century”, it was more than a bit presumptuous. When the Lit Hub staff discussed it in our editorial meeting that week, we immediately began rattling off books we assumed would have been on the list but weren’t – thus our (also incomplete list) was born. I’m still upset that I didn’t write a blurb for Yiyun Li’s The Vagrants or David Grann’s The White Darkness, but I’m glad that we were able to highlight a lot of very good books that should have been recognized, and I hope the paper of record takes another stab at it once, you know, more than a quarter century has passed. –EF

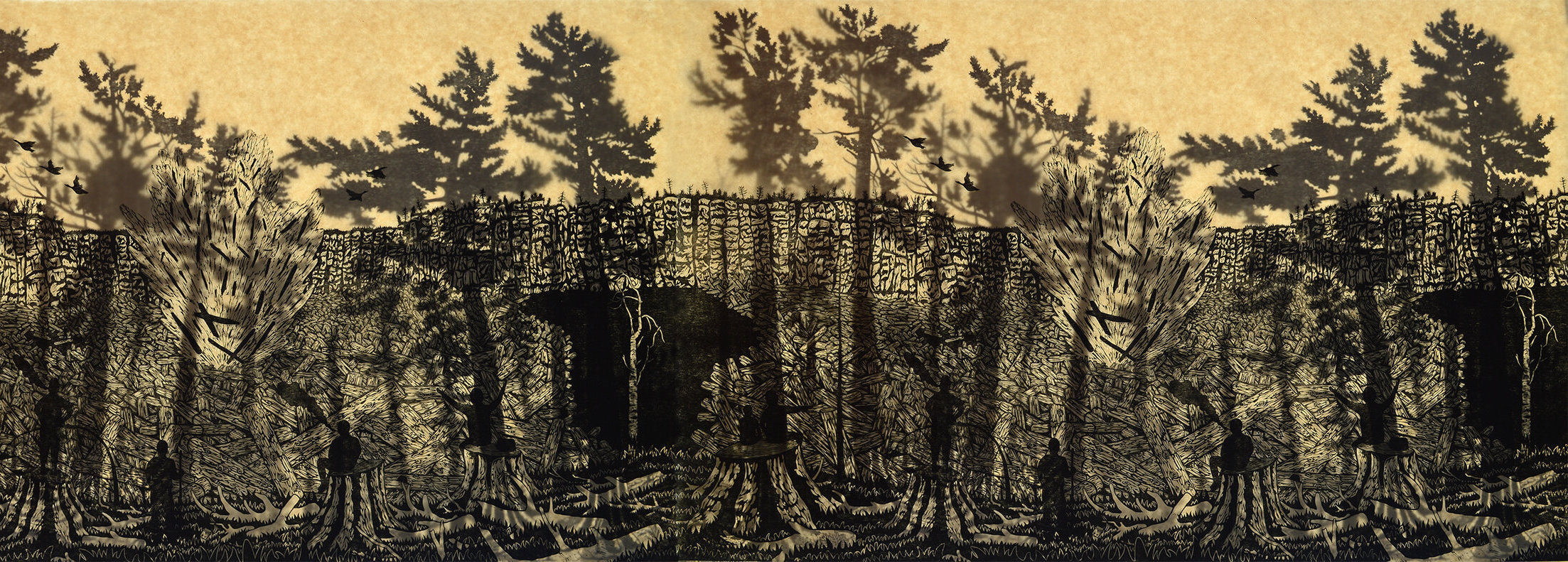

The Crooked Timber of the Mind: On the Rise of “Autojournalism”

by Robert Moor

It’s not often you get to publish a piece of criticism that makes a deeply substantive case for an entirely new genre of writing, and does so with such playfulness and delight that you wish it would never end… Actually, this never happens. And yet I still find myself thinking about Robert Moor’s incredible February piece about the rise of “autojournalism” and its intimate and erudite reading of Matthew J.C. Clark’s Bjarki, Not Bjarki. Moor is effortless as a writer, his ideas complex and original, his prose crystalline and enticing:

“Because journalists have erased themselves from their own stories for so long, it is easy to forget how profoundly weird—in the old sense of that word—it feels to actually be a journalist: to sit in a room and ask probing questions of strangers; to follow them around and dig through their (real and metaphorical) dustbins; to collect details, like so many stray hairs and nail clippings; and then to use that sparse and disconnected material to try, via a kind of magic incantation, to create something living (or at least, life-like). Deep down, it’s a creepy, witchy business.

Here, a fourth genre (far smaller than the rest) hoves hazily into view—one where the journalist refuses to hide just how uncanny and uncomfortable his job is, on a moment-to-moment basis. Only this genre is peopled not by professional journalists, but by novelists who have been bribed into writing magazine stories, writers like Karl Ove Knausgaard, George Saunders, David Foster Wallace, William T. Vollmann, and Emmanuel Carrère. As one might expect, their attempts at reportage often take on the texture of fiction—the perspective (usually) embodied and temporalized rather than abstract and authoritative; the language (always) polished to a high gloss—with the main character being the hapless novelist-turned-journalist. Though their voices vary, what they all have in common is the way they treat the thoughts (and, more pointedly, the insecurities) of their narrators with equal weight to the things they observe happening in the world around them. In fiction (especially autofiction), this is the norm; in journalism, it is anathema.”

–JD

Comedy failed us, again.

by James Folta

James Folta is doing bang-up work across the board but this might be the best of his run on the site so far. The discourse around comedy in These Times has lacked this kind of thoughtful take—one that examines why it isn’t just the “you can’t say anything these days!” comics but also the “taking the easy lay-up” comics who are failing to meet this moment. Humor requires more work than just being mean to people who can’t defend themselves, and even the most searing satire isn’t going to scorch the hydra that is right-wing authoritarian revanchism. But also we want—nay, need!—to laugh. James, thankfully, gets it. –DB

Love in the Time of Hillbilly Elegy: On JD Vance’s Appalachian Grift

by Justin B. Wymer

Unfortunately, the events of the past have dragged Hillbilly Elegy to the front of our collective minds. As a necessary palate cleanser, I recommend Justin B. Wymer’s gorgeous meditation on growing up in West Virginia and dealing with the personal grief wrought by the opioid epidemic, as well as the nefariousness of Vance’s cynical exploitation of the region. –JG

Somaia Abu Nada Remembers Her Slain Sister, Heba Abu Nada, Palestinian Poet and Novelist

by Somaia Abu Nada

A beautiful, beautiful obituary. “Everything genuine reminds me of you, Heba,” writes Somaia Abu Nada about her sister, and I wish each and every victim of genocide could be remembered so lovingly. This eulogy for the acclaimed poet and novelist is a reminder of the titanic enormity of the destruction in Palestine: each death erases so much, and the attempt at collective destruction of a people is a loss of individuals at scale, the blinking out of a constellation by erasing points of light one by one. –JF

A Literary Road Trip Across America

This year we published the travel guide I never knew I always needed: a state-by-state map of the country that recommends books, literary landmarks, and the best places to read. (Also of use: the extra recommendations in the comments.) –ET

Susan Abulhawa Remembers Refaat Alareer: Poet, Teacher, Husband, Father

by Susan Abulhawa

Susan Abulhawa’s tribute to the life and work of the beloved Palestinian poet and activist Refaat Alareer, who was killed in a targeted Israeli airstrike in Gaza last December. It’s a beautiful portrait of a beautiful soul—somebody who dedicated his life to literature and to the liberation of his people:

“He believed people were essentially good; that if they could only see what was happening to us, they would stop supporting our colonizers; that if they could see the magnificent beauty of our souls, they might love us. He also wanted to ensure our lives would be recorded despite rampant efforts to erase our presence in the world.” –DS

Amitava Kumar on Finding Solace in the Words of Others

by Amitava Kumar

In thinking about his father’s death, Amitava Kumar pulls together the wisdom of other writers—friends like Hanif Kureishi, writers he admires like Annie Ernaux and Louise Glück, and a passage from a book he recently reread by Martin Amis. In the most difficult times, good writing can help put into words what we cannot, although Kumar, here, gets very close to saying it perfectly. –EF

How Vulnerable Low-Wage Workers Power AI Algorithms

by Madhumita Murgia

So many discussions about AI tend to reinforce the marketing narratives these companies are inventing. But the reality of how this tech works can’t be unplugged from the people and the resources that power them and Madhumita Murgia’s essay on the “ghost work” that forms the “undervalued bedrock” of AI is a sobering reminder of the cost these machines extract. AI is neither artificial nor intelligent, but rather the labor of many people obscured by marketing hype. Like so many products of consumer capitalism, the Great and Powerful Oz of AI is a drawn curtain hiding underpaid and exploited workers. –JF

What to read after watching I Saw the TV Glow

by Drew Broussard

I know, I know—submitting my own piece?? EGO MUCH??—but this one’s important to me. For one thing, it’s the single piece I wrote this year that felt like it provoked the most genuine conversation with friends and strangers on the internet. My POD piece had a wider reach (and got me yelled at far more) but this is the one that got folks talking, it seemed, in a generative way. Maybe that’s because Jane Schoenbrun’s film (which, by any rights, should be a part of the Oscar conversation on several levels and it’s an indictment of modern culture that we have such paltry and middling films being lifted towards glory but I digress) has remained in my head since seeing it this spring, maybe it was because I just like recommending a bunch of books at any old time and these were really good ones, or maybe it’s because of the particular alchemy where these books and that film felt like a true web of interconnectivity that inevitably sends a reader (or viewer) farther down other paths because all art is in conversation with all other art and isn’t it fun to expand and explore said paths? –DB

Between the Lines: What Is Missing in the Diversity in Publishing Discourse

by Thomas Gebremedhin

Thomas Gebremedhin is a brilliant editor, and his essay about his experience as Black man in publishing is an essential—and beautiful—read. Gebremedhin writes about the way in which people of color in the publishing industry are reduced to “window dressing” in the larger scope of the diversity discourse. As an editor, he is keenly aware of the dangers of neglecting the full, beautiful scope of experience in favor of a tidier narrative. Writers and readers alike would do well to take note. –JG

The Byronic Revolution of Che Guevara

by Ed Simon

Ed Simon’s essay is a wonderful comparison of two famed international freedom fighters, who came to define the archetypal “dashing hero who traipses the globe on behalf of liberation, emancipation, revolution.” I find Byron’s enthusiasm and dedication—especially for the Luddites—to be inspiring in our current time of monsters, and Simon’s piece is an excellent exploration of how he became the idealized handsome freedom fighter. –JF

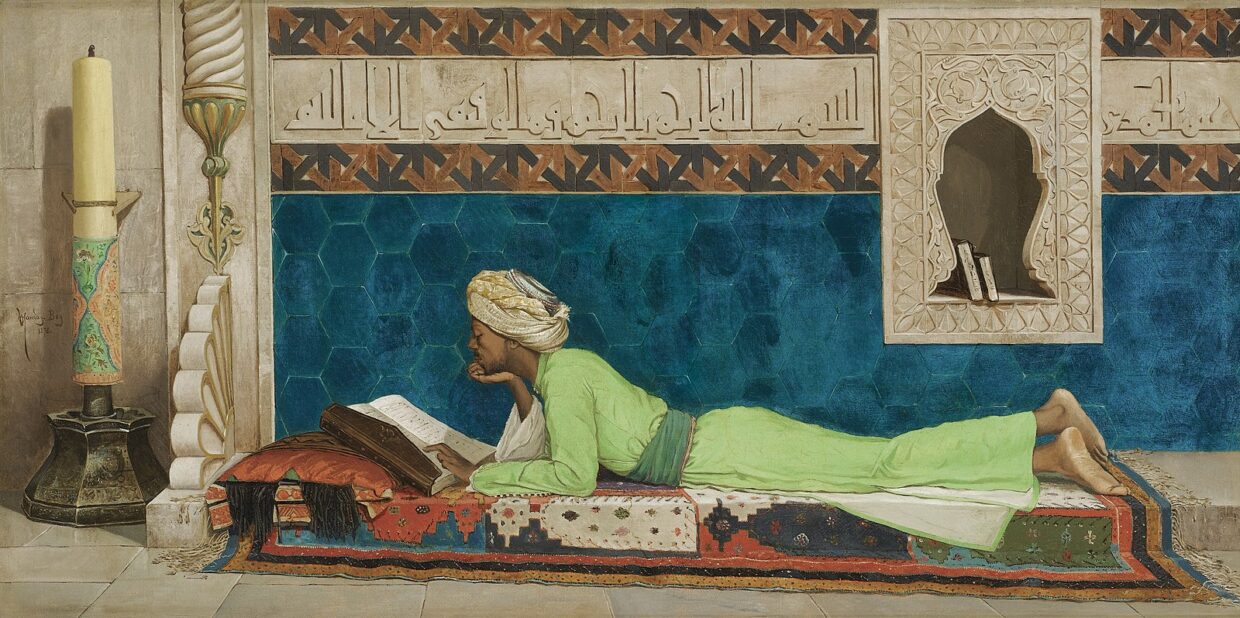

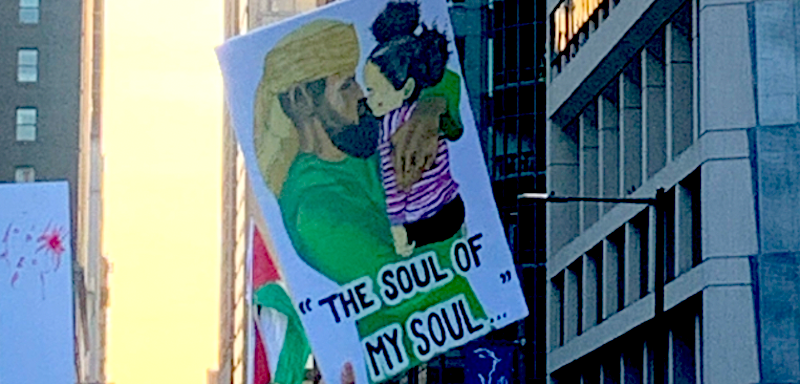

“The Final City.” A Poem by Samer Abu Hawwash, translated by Huda Fakhreddine

An elegy in the voice of Khaled Nabhan, the Palestinian man who last year held his murdered three-year-old granddaughter Reem to his chest and called her “the soul of my soul” as he said goodbye. Every time I read this achingly beautiful poem, my heart is broken anew:

“In the ruins of this final city,

in this night of nights,

by your small bed

torn apart by monsters,

I stand naked,

stripped of myself

and of everything.”

–DS