When news broke of the NWSL’s application to form a Division II league, the one question that did not need to be answered was why. Commissioner Jessica Berman made it public knowledge over the last few months that investing in the pathway from the youth levels to the professional game would be a priority in the NWSL’s next chapter of growth, and few need to be convinced that there is room for improvement in the current American women’s soccer landscape. Look no further than the fact that there presently are no Division II leagues for women in the U.S., nor any true reserve leagues that have long been the preferred avenue for young talents to transition to the big leagues.

Identifying a glaring need, though, is different than successfully filling a gaping hole in the player development process. How the NWSL plans to get this Division II league off the ground is equally as important, if not more important, as why it feels the need to do so. The application answers some questions, mainly that they plan to have eight Division I teams on board for the inaugural season in 2026 and the rest by 2030. Other details, be they about compensation, the impact on the NWSL’s plans to expand and how closely it resembles other reserve leagues, will have to wait.

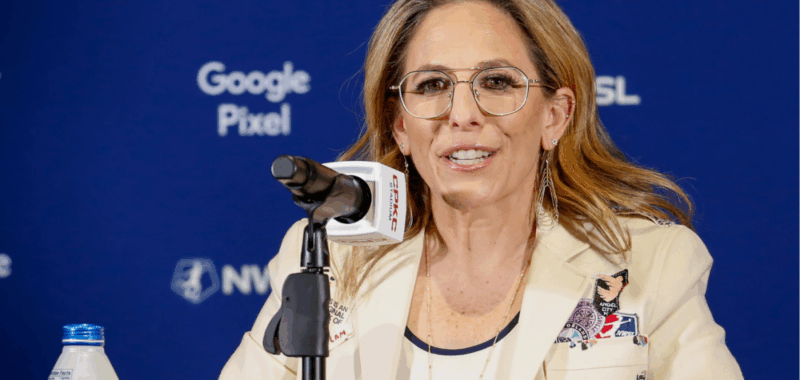

“The short answers,” Berman said at the Associated Press Sports Editors commissioners meetings on Tuesday, “are basically, ‘don’t know, don’t know, don’t know.'”

Footing the bill

The NWSL’s application to launch a Division Ii league included the logistical bare bones of a league – a plan that the eight teams lined up for the inaugural season would play in the stadiums as their Division I counterparts (Bay FC, Kansas City Current, North Carolina Courage, NJ/NY Gotham FC, Orlando Pride, Racing Louisville, Seattle Reign and the Washington Spirit). There are lines about opportunities for young players, inexperienced coaches, developing referees and a chance for marketing teams to try innovative ideas. How it all comes together is a big question, though.

An entirely new league is no small undertaking, regardless of the scale of the operation and the spot on the pyramid. Operating a team in the USL Super League, for example, reportedly costs around $3.4 million to $7.7 million annually, per Backheeled, and that is without considering the literal act of making sure everything is in place by next year, the NWSL’s proposed start date. Berman said it’s all in a work in progress.

“I know on NWSL terms, six months is a long time,” she said. “I do know that the application process with U.S. Soccer is iterative and so you have the opportunity to continue to work with them on all of the development plans as you march towards the potential launch and so we’ll be working in lockstep with them as we continue to make decisions about the how, what, when, where.”

Still, limited specifics with about a year to go is not ideal for the many that exist inside the NWSL’s orbit. That includes the many – players, coaches, referees – who have not heard word on how they will be compensated for taking part in the proposed Division II league, something the NWSL Players Association has flagged.

“The NWSL Players Association is closely monitoring the development of any expansion or Division II leagues created, maintained, or sanctioned by the NWSL,” executive director Meghann Burke said in a statement to CBS Sports. “If the NWSL expands its footprint, it must do so in a way that respects the value, contributions, and livelihoods of every player it employs, directly or indirectly. We stand ready to engage with the League to ensure that any new league model honors these obligations, as well as to ensure the League complies with the rights of our members memorialized in the CBA.”

There is also an open question about facilities, in part because most NWSL teams do not own their training grounds and stadiums. It is worth asking how many available dates there are for a new batch of games at these venues, while finding new training space – either at the property the Division I teams already use or elsewhere – is also a logistical issue that needs to be solved. Next year will be particularly challenging from that standpoint, too – FIFA will be using a wide range of facilities for next summer’s men’s World Cup, both in terms of base camps for the 48 national teams that will participate and for additional training sites in the buildup to games.

“When we realized that two, three years ago, our season was going to overlap with the men’s World Cup, in my mind, we’re playing the whole time,” Berman said. “Why wouldn’t we? We then learn that they’re talking over all of our buildings, by the way. Oh, that’s good to know, and so it is forcing us to evaluate how we can show up and when we can show up but this is not our World Cup. … What that looks like and how that sticks with all the logistics that sometimes can stand in the way of innovation — stadium availability, broadcast windows, all those things — is what we’re working through right now. If someone could manufacture 16 buildings for us to play in, we play.”

‘They have a lot of work to do’

For many, there has been a long need for a reserve league in American women’s soccer, where the college game remains the primary player development pathway but is slowly becoming less relevant. Players are signing professional contracts at younger ages, several bypassing college soccer altogether – the Washington Spirit’s Trinity Rodman was among the first while NJ/NY Gotham FC’s Mak Whitman became the NWSL’s youngest-ever player when she signed a deal at age 13 in July. While Rodman was ready to play amongst professionals, winning Rookie of the Year in 2021, the same is not true for everyone, almost making the NWSL’s proposed Division II league a no-brainer for several reasons.

“I think there is definitely a big gap that, at the moment, we need to fill,” Gotham head coach Juan Carlos Amoros said on Friday. “I think that structure, how it is, is very challenging. You could see that a perfect example is we got a couple of injuries in the goalkeeper position and obviously because of our roster and not having a B team, we almost had to ask Michelle Betos, who is a member of the staff now, to come back and play or you want to have young players and they have to be in the first team roster but it’s still very difficult for them to get minutes because if they are in the first team roster, you cannot have them or you cannot control or support their development.”

Simply launching a Division II league would not magically solve all the problems, though. Chief among them is that the NWSL’s Division II league could be part of a fractured landscape as soon as U.S. Soccer signs off on it – the WPSL Pro has also applied for Division II status, and there’s nothing stopping the sport’s governing body from approving both applications. There are currently two Division I leagues on the women’s pyramid (the NWSL and the USL Super League) and in the men’s game, two Division III leagues (MLS Next Pro and USL League One), while the USL has applied to have a Division I league for 2027 while MLS already has that status.

It’s a unique set-up compared to other soccer pyramids around the world, where it is rare to have more than one league at the same level. There’s an argument to be made that it makes the whole prospect of player development more confusing, though, be it an identity crisis for a league that has to share a slice of the pyramid with another or the simple fact that a fractured landscape may not actually be ideal for player development.

“it’s going to be good for the league but they have a lot of work to do – how to put this together and make it look good,” Lorne Donaldson, the recently fired Chicago Stars head coach with an extensive body of work in the U.S. youth game, said on Friday. “All the logistics [have] to be good to make it run properly because we still have college and college is not going anywhere.”

There is also a question about whether or not there are enough players to fill the roster spots in two Division II leagues, especially as many players still choose the college route. The NWSL’s Division II league plans to start with eight teams next year, while the WPSL Pro aims to have 12 in 2026, all of whom could be competing for the same players. Donaldson is convinced there are enough athletes to earn spots on rosters, though it might require going global.

“I think there are players there,” he said. “If it takes players coming out of Africa, there’s a lot of players, not just in the USA. [There are] players coming out of Brazil. I think with some of these young players, readily come over and play in these leagues because they’re not college-bound, most of those players. They just want to come at 15, 16, 17. They just want to go right into our pro league like they do in Euro countries and I think if they have the opportunity, yes but I also think we have enough players in this country, lots of good players in this country that I don’t see that as a problem.”

That plan might be a departure from MLS Next Pro, the Division III men’s league that MLS uses as a feeder for domestic talent. Berman acknowledged that the NWSL feels no specific need to follow that model and that the expertise of team owners who have presence in MLS and the NWSL will be valuable.

“I think we have the benefit of having a lot of smart, experienced MLS owners who are part of our ecosystem who have helped to steer that strategy and say, let’s look at what MLS Next Pro has done and let’s analyze what our goals are and let’s think about what we can we learn about and what we might want to do the same or differently,” she said. “The great part about being at this league is that all options are on the table. Again, you have the ability to innovate and ask ourselves, ‘Is the way it’s been done before the right way for us?’ and give ourselves permission to say yes or no and evolve our strategy from there.”

The future of expansion

The application also included one short sentence with sizable implications – the NWSL “will provide opportunities for unaffiliated clubs to join the Division II League.”

There were also no specifics on a timeline for Division II expansion, though that is not necessarily unusual. The expansion process is inherently one that comes, consistently evolving depending on the demands of the league a new team hopes to enter. That is equally true for the NWSL’s current Division I league, where more rounds of expansion are almost a guarantee even if a timeline for the next round is not currently clear. The Division II league, Berman said, definitely introduces a new type of expansion race for the NWSL, and perhaps a needed one since she said they entertained 80 bids of all shapes and sizes in their last round, which ended earlier this year with the selection of a Denver-based ownership group.

“Division II is one of the potential ways that we’re evaluating to determine how we ensure that we are in a position to continue to expand and to continue to grow and that we have the sourcing of high quality talent from a player and technical staff perspective and all that is still under analysis,” Berman said. “Filing for Division Ii gives us optionality to be able to launch as we continue to assess the demand for interest in expansion in sometimes smaller markets that are wanting to be part of the NWSL ecosystem and help us get after some of our sporting goals and so all of those things are currently in what I describe as the sausage-making process.”

Many, if not all of the much-awaited answers, are expected to be formalized through U.S. Soccer’s application process. U.S. Soccer’s board of directors, a group that includes Berman, will vote on both the NWSL’s Division II application and WPSL Pro’s submission at a later date.