When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

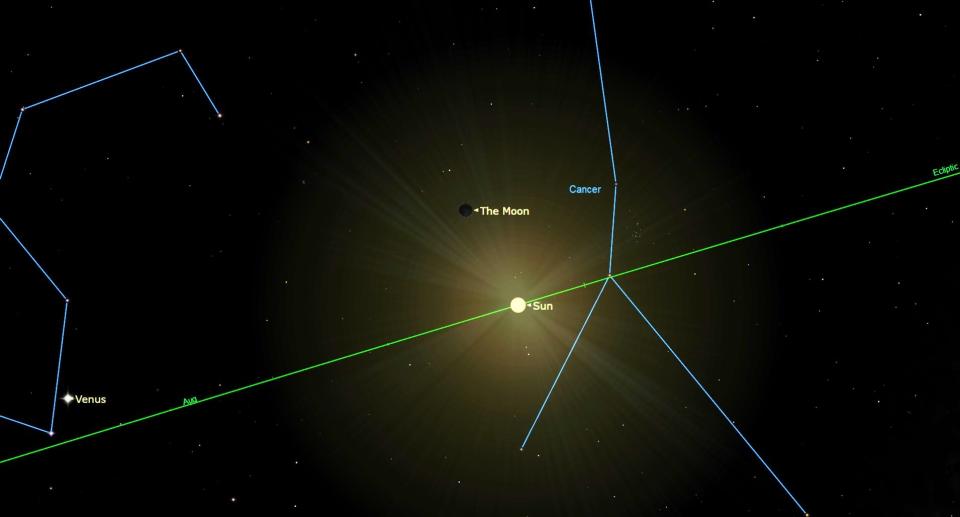

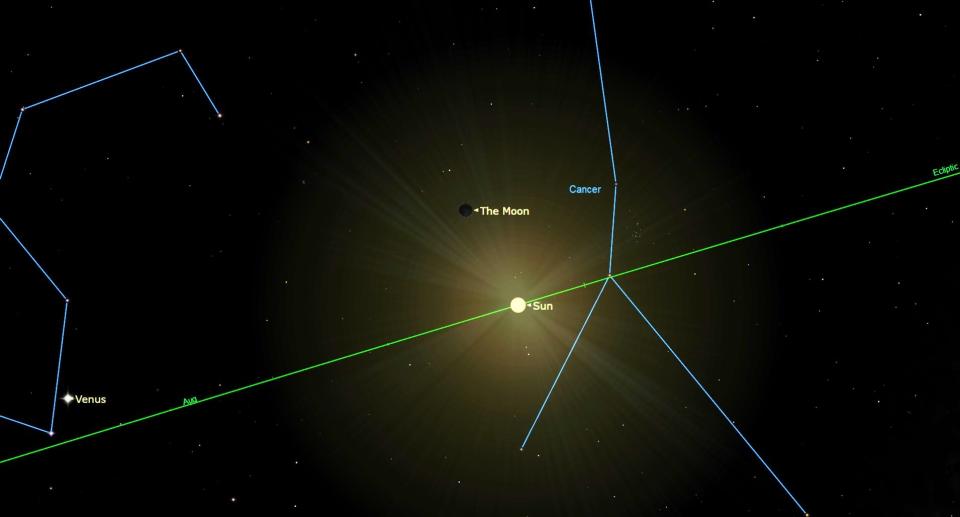

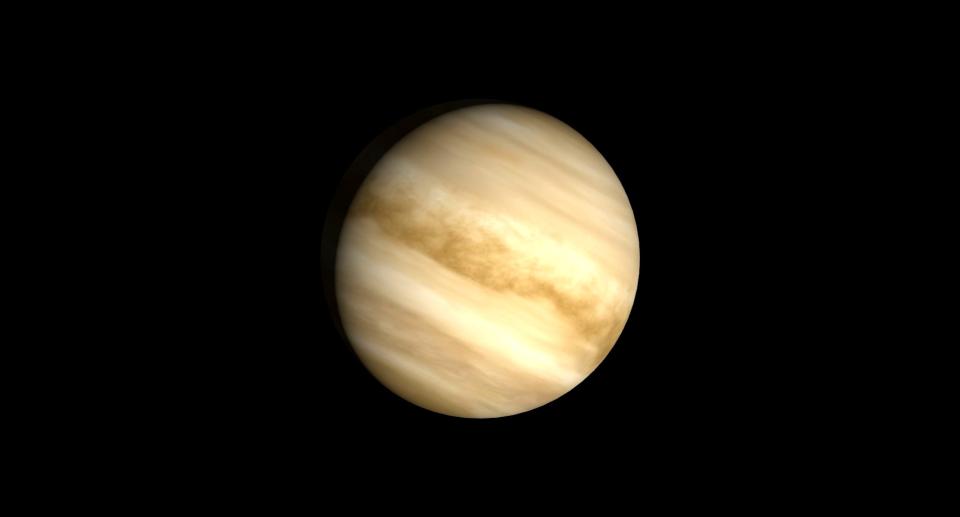

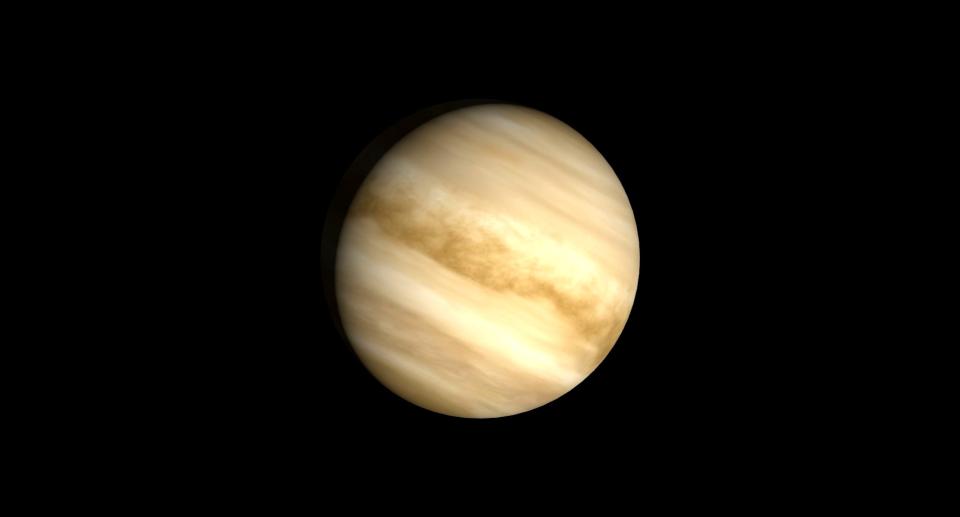

The new moon occurs Aug. 4, at 7:13 a.m. EDT (0113 UTC). In the days following the new moon, our satellite will make a close pass to Venus; after that Venus and Mercury will be close together, making a visible pair in the evening sky.

A new moon describes the moment when the sun and moon share the same celestial longitude; this is called a conjunction. This happens about every 29.5 days. As the illuminated side of the moon faces away from Earth, new moons are invisible to ground-based observers unless the moon passes directly in front of the sun, which creates an eclipse (the next time that happens will be Oct. 2).

New moons are often the way lunar calendrical systems mark the start of the month; in Muslim traditions in particular the month started as soon as observers could see the thin crescent moon after sunset (this is one reason why the crescent moon appears often in Islamic iconography). Jewish, Māori and Chinese calendars also use the new moons in this way.

The timing of new moons (or any lunar phase) depends on the position of the moon, rather than one’s position on the Earth, so to find the time of the new moon locally one need only look at the time zone; on the Eastern Seaboard the clocks are four hours behind Universal Time, in Los Angeles is seven hours difference so the new moon is at 4:13 a.m., while Sydney, Australia is 10 hours ahead so the new moon is at 9:13 p.m. Aug. 4.

If you’d like to get an up close look at night sky during new moons, be sure to take a look at our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars.

And if you want to photograph the night sky, we have tips for how to shoot the night sky and how to photograph the planets, as well as guides to the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Conjunction of the moon and Venus

For middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere — approximately the continental United States, Japan, much of China, Europe between England and Gibraltar, and the northern coast of Africa — the sun fully sets by about eight p.m. and the sky gets dark by about 9 p.m. sunset is a bit later at the extreme northern end and earlier at the extreme southern end of this range.

On the night of the new moon (Aug. 4) one will see Venus in the western sky; the planet sets at 8:58 p.m. in New York City, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. Being the brightest celestial object behind the sun and moon, Venus is often one of the very first “stars” that one can see after sunset. Civil twilight — the time where the sun is between the horizon and 6 degrees below the horizon — ends in New York at 8:37 p.m., 30 minutes after sunset. At that point Venus should just become visible. (The end of Civil Twilight is also when New York State requires car headlights be turned on).

The next day the moon will be in conjunction with Venus, passing just under 2 degrees (about four lunar diameters) to the north of the planet. The conjunction happens at 6:03 p.m. Eastern time, but the pair won’t be readily observable at the latitude of New York – at sunset (Which is at 8:06 p.m. local time) Venus is only 9 degrees above the western horizon and by 8:36 p.m. it is less than 4 degrees high –less than a handspan held at arm’s length.

If one can spot the day-old moon — it will be a very thin crescent — it can be used to locate Venus, which from New York’s latitude will appear to be slightly to the left and below the moon; but against a still-light sky one will need a clear, flat horizon and near-perfect conditions.

The conjunction is easier to see as one moves southward. In Miami, the conjunction is still at 6:03 p.m. local time, according to In-the-sky.org, but it will be higher in the sky at sunset — which is at 8:04 p.m. — Venus will be at an altitude of 12 degrees, and by 8:15 the moon and Venus will be just becoming visible and Venus will be about 10 degrees high, below and to the left of the moon. Observing the two will still require an unobstructed horizon (over the ocean or other large body of water, for example).

Prospects get better as one gets to the tropics (technically, south of 23.5 degrees north or north of 23.5 degrees south). In San Juan, Puerto Rico (latitude18 degrees north) the conjunction is at 6:03 p.m. local time, and sunset is at 6:57 p.m. At sunset Venus is at about 13 degrees above the western horizon and to the left of the moon (as one moves south the apparent position of Venus relative to the moon appears to move upwards). In the tropics, sunsets tend to be “faster” — the sky gets dark more quickly as the sun’s angle of descent to the horizon is steeper — so the pair will be visible sooner; the sky gets just dark enough to see them by about 7:10 p.m.

In the tropical latitudes it’s also possible to see Mercury, which is also in conjunction with the moon on Aug. 5; the innermost planet will be relatively far from the moon — about 7 degrees — but from Puerto Rico it will appear almost level with the moon and to the left. From higher latitudes the planet is too low in the sky to see by the time the sky gets dark enough; but in more southern locations the quicker sunsets and the ecliptic being at a steeper angle to the horizon combine to put Mercury higher up.

In Singapore, the conjunction itself happens at 6:03 a.m. local time on Aug. 6., so the moment when the moon gets closest to Venus won’t be visible. That said, at sunset (7:15 p.m. local time) Venus is nearly 16 degrees high; by this time the moon has moved (relative to the background stars) so that Venus will appear below and slightly to the right of the moon, though it won’t be visible until about 7:30 p.m. At that point Mercury will also start to come out; it will be to the left of the moon and Venus making a triangle.

For mid-latitude Southern Hemisphere observers the days are shorter and the sun sets sooner, which puts Venus and the moon both in a slightly better position than for their Northern Hemisphere counterparts. In addition, the sky appears “upside down” so that objects in the southern half of the sky in the Northern Hemisphere are at higher altitudes in the Southern Hemisphere.

For example, in Santiago, Chile, the conjunction of the moon and Venus is at 6:03 p.m. local time and sunset is at 6:07 p.m. At about 6:30 p.m. Venus is about 10 degrees high, and in contrast to the Northern Hemisphere the planet will appear above the moon and to the left. Mercury, meanwhile, will be about 14 degrees high and to the left of Venus, making it much easier to spot.

Visible planets

On the night of the new moon, Saturn is the first visible planet after Venus sets; in New York the ringed planet rises at 9:40 p.m. local time in the constellation Aquarius; it reaches its highest altitude at about 3:19 a.m. (Aug. 5) when it will be 43 degrees above the southern horizon.

Mars and Jupiter, meanwhile, are both in the constellation Taurus, the Bull. They rise in the wee hours of Aug. 5, Mars first at 1:12 a.m. EDT in New York, and Jupiter follows at 1:30 a.m. The two planets will be near Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus, and from mid-northern latitudes Mars will appear at the top of the triangle they form, with Jupiter marking the left corner. Aldebaran and Mars will be distinct because of their reddish hue, with Aldebaran appearing more orange.

From the Southern Hemisphere, the triangle formed by Mars, Jupiter and Aldebaran will appear rotated counterclockwise, so that Jupiter marks the lower corner, Mars is above and to the left, and Aldebaran is almost directly above Jupiter. From Melbourne, Australia, for example, Mars still rises first in the northeast at 3:07 a.m. local time on Aug. 5, and Jupiter at 3:30 a.m. Aldebaran comes up at 2:52 a.m. It is winter in Melbourne, so sunrise isn’t until 7:16 a.m.; about a half hour before sunrise Mars is 28 degrees high and just east of north.

Constellations

Even with the relatively shorter nights, August skies offer Northern Hemisphere observers a chance to see constellations of three seasons – traditional summer, autumn and winter – and from darker-sky locations to see the Milky Way as though one were facing both the center of the galaxy and the outer rim.

By about 10 p.m. on Aug. 4 the sky is completely dark, and even from city locations it’s possible to see the constellations Lyra, Cygnus and Aquila, high in the southeast. Lyra is the highest, with Vega, its brightest star, 82 degrees high at the latitude of New York City. Left (east) of Vega is Deneb, the alpha star of Cygnus the Swan, and below (southwards) is Altair, the eye of Aquila, the Eagle. These make up the Summer Triangle asterism. From a darker sky site one can see the Milky Way, the misty band of light that shows the edge of our galaxy, and in the direction of Cygnus one is looking towards the galactic east, about 90 degrees away from the center.

Just above the southern horizon will be Sagittarius and Scorpio; here you are looking towards the galactic center; and the Milky Way is appreciably brighter and wider. The brightest star in Scorpius is Antares, which is about 19 degrees high and just west of south. One can use Antares to spot the claws of Scorpius – three stars that form a roughly vertical line to the right (west) of Antares. From there one can go back to Antares and trace a curved line of fainter stars that form the Scorpion’s back and tail.

Continue upwards from the end of the tail and one hits Sagittarius, notable for its “teapot” shape. The brightest star in Sagittarius is called Kaus Australis, it is in the bottom right corner of the “teapot.” Sagittarius and Scorpius are the southernmost zodiacal constellations; parts of them are not even visible from the latitudes of northern Europe.

Above Scorpius, one can see a large five-sided, narrow “box” of stars; this is Ophiuchus, the Serpent-bearer or Healer. On either side of the box are fainter groups of stars; on the right is Serpens Caput (Head of the Serpent) and on the left is Serpens Cauda (the Tail of the Serpent). Ophiuchus is sometimes called the thirteenth Zodiac sign because the sun actually passes through the constellation from Nov. 29 to Dec. 18; however the reason this happens at all is that the path of the ecliptic relative to the stars has shifted since the classical Zodiac was devised; in addition the modern borders of constellations, set in 1928, didn’t take astrology into account.

Facing north, one can see the Big Dipper, part of the Great Bear, Ursa Major, to one’s left (westward). The “bowl” of the dipper points to the right, and one can follow the two stars in the front of the bowl to Polaris, the Pole Star. The two stars will be on the bottom side of the bowl at that point in the evening. Using the handle of the Dipper one can “arc to Arcturus” by tracing a sweeping arc along the handle to the first bright star one encounters. Arcturus is the brightest star in Boötes, the Herdsman. Opposite the Big Dipper, about the same distance to the right (eastwards) of Polaris and about 30 degrees high, is Cassiopeia, a W-shaped group of stars.

By midnight the Summer Triangle has moved almost directly overhead. From the left side of the Summer Triangle, one can turn east (left) and encounter a large square of medium-bright stars; the top corner of the square is about 45 degrees high. This is the Great Square of Pegasus, the legendary winged horse ridden by Perseus the Hero. The square will look as though one corner is pointed to the horizon; the three stars that make up its right side are often counted as Pegasus’ wings.

The left corner, meanwhile, is the head of Andromeda, the woman who, according to legend, Perseus was saving from the leviathan Cetus, (also called the Whale). Cetus isn’t high enough to see yet – it is just rising. All of these constellations appear earlier in the evening as summer turns into fall.

By 3 a.m., using Jupiter and Mars as landmarks, one can look to the east and see Taurus the Bull rising, with the head of the bull marked by the open cluster called the Hyades. That cluster surrounds Aldebaran, though it isn’t associated with the star, it just happens to be in the line of sight. Meanwhile, looking to the north of Taurus (to the left) one can see a bright star a bit higher than Aldebaran, called Capella, in Auriga, the Charioteer. Both constellations are associated with the winter sky. The Milky Way continues here through Auriga, Perseus, and Cassiopeia; the direction of Auriga is towards intergalactic space, exactly opposite the galactic center seen in Sagittarius.

In the Southern Hemisphere August is late winter, with the sun setting relatively early. From mid-southern latitudes by 8 p.m. one will see Crux, the Southern Cross, about 45 degrees high in the southwest. Above it is Alpha Centauri and the constellation Centaurus, the Centaur. (You can find Alpha Centauri by drawing a line up along the crossbar of the Cross).

Below the Cross and extending to the southern horizon are Carina the Keel and Vela, the sail, two of the constellations that make up the ship Argo, which Jason sailed. Vela is a rough oval of 10 stars, though only eight are readily visible from more urban locations. Carina occupies the space between Vela and Crux. From the latitudes of cities such as Santiago, Chile, Antares is almost directly overhead; to the right (as one faces south) is Libra, though it is a rather faint constellation. If one follows a line starting at Antares and going through the southernmost star of the claws, one reaches Spica, the brightest star in Virgo.