I prefer to write in my grandfather’s shirt. I’m wearing it now, a blue-and-white-striped Brooks Brothers button-up he passed down to me as a teen. It’s one of several garments I have of his, among them a Christian Dior dress shirt, a broadcloth button-down from Barneys New York’s private label, and a pale pink tie with a diagonal stripe pattern by Oscar de la Renta. I cherish them because they’re his; they express his style. And when I wear that shirt I feel most at home, so to speak. But I also take pride in wearing or simply having his clothes because he’s a Renaissance man.

Eight years ago, for the Butler Institute of American Art’s Black History Month programming, my grandfather curated a self-titled exhibition, “Maj. Amos Randall Sr.: Love You Greatly,” which included a self-portrait he drew in elementary school and other illustrations of his own work. (“LOVE YOU GREATLY” is his signature sign-off, even when texting. All caps, always.) As a Vietnam War hero, he was inducted into the Ohio Military Hall of Fame in 2005, receiving numerous awards for his service and leadership. He’s a devoted woodsman. And during the cozily structured summers I’d spent with him—writing essays and book reports for prompts he’d given me, most memorably—he was one of my earliest editors. I texted him last June asking if he still kept stacks of books and newspapers at the foot of his bed. It’s no surprise that he does; his astute, creative, affective word use is present as ever.

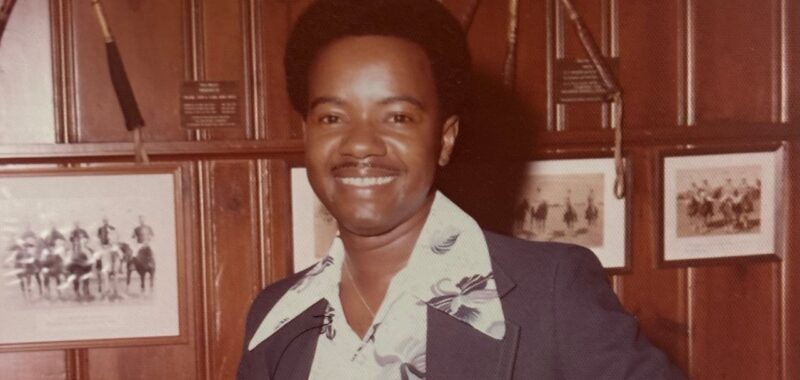

Courtesy of Julian Randall

For what now seems a rather prescient family history project I was working on, I once had him send photos of his clothes. The man’s got taste. Herewith his “ASSORTMENT OF ATTIRE”: feathered Stetson hats, a London Fog trench coat, his collection of ties mirroring my preference in them—go bold or bust! Not to mention his three or so Pierre Cardin boots from when the designer was better known for menswear. He has a fine eye for clothes that he has applied to his art, as seen in another of his self-portraits, all dandy-like in a white, peak-lapel suit and burgundy polka dot tie with a matching pocket square.

To paint the full image of my grandfather sporting such clothing would mean including these accessories: cologne and a nice car. Smelling good, like a good haircut, has always been as vital to Black men’s style as our clothes. And his cars were parked in a neighborhood with only three Black families, in Lawton, Oklahoma, where he still lives. When my mom was growing up, he drove “a pearl white 300 ZX with cognac leather interior. Always detailed and nice and clean,” she recalls. By the time she was in high school, “he drove a white Lexus with chrome wheels.” Maj. Randall took pride in all facets of his appearance.

Throughout his life, my grandfather has kept that up with the disciplined consistency one expects from an army veteran. “We were always concerned with ironed clothes, crisp clothes, starching our clothes,” Phillip Randall, my grandfather’s brother, tells me. The two were inseparable growing up, sharing personality traits and an appreciation for fine clothing. Recounting how my grandfather’s time in the military informed his style, Uncle Phillip added, “Amos was always neat and pressed. He wanted to have the best look, but not overtly so.” It’s just that “you would expect all that to be in the uniform.”