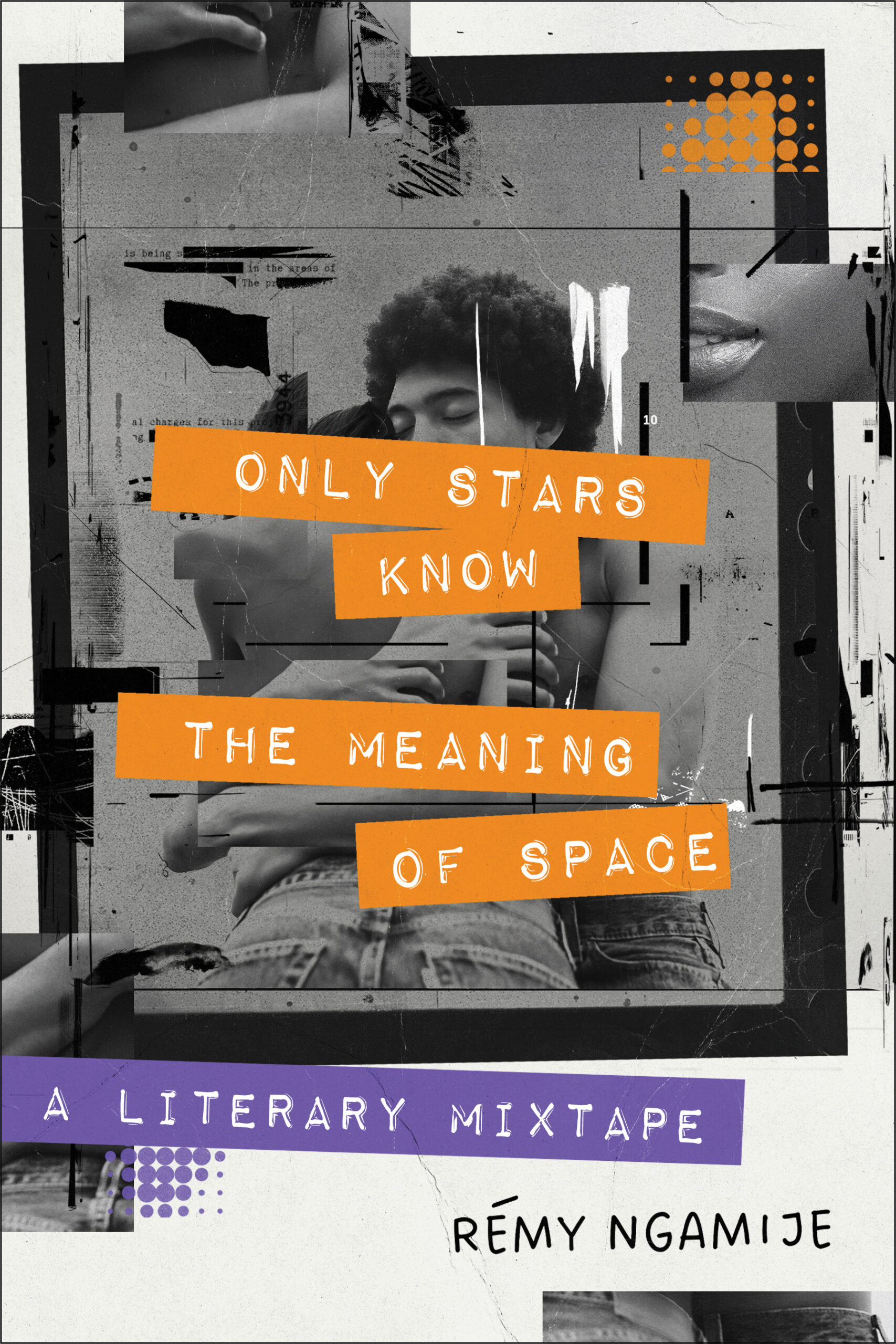

The following is from Rémy Ngamije’s Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space. Ngamije is a Rwandan-born Namibian writer and photographer. He won the Africa Regional Prize of the 2021 Commonwealth Short Story Prize and was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2021 and 2020. He is the founder of the Doek Arts Trust, an arts organization which publishes Doek! Literary Magazine, the country’s first literary magazine which he cofounded and serves as editor-in-chief.

The good old days. That’s what everyone calls them. I just remember them as being old. Dry, dead, endless heat. Days hiding from the sun. Nights with only stars for witnesses. Hours of nothingness, waiting outside a village, tracking movements. And minutes filled with whizzing bullets. Paah-paah when they left the gun. Chook-chook when they hit the sand just in front of me. Or whoosh-whoosh as they zoomed into the trees and bushes behind me, stripping them of foliage—it’s easy to remember the sound of bullets when they don’t hit you.

There! A target.

Article continues after advertisement

Take aim, breathe—fire!

Terrorist down.

Do it again. And again.

“The good old days, eh?” Pietermaritzburg reminisced as we sat on his farm’s stoep. Intel.

Enemy movements. Missions. Targets. Clear and defined.

“Ja,” I replied, “the old days.”

Looking at dirt paths, trying to see if the earth had been disturbed by mine planting. The evenings, humid, sticky, full of malaria and the harrumphing of hippos when we were near the Okavango. The mornings of creaking muscles—the nerves, stretched, steeled, and sharpened. The monk-like blanking of the mind, the vacating of the soul. No wants or desires beyond the day’s hunt: insurgents, guerrillas, rebels, freedom fighters, terrorists—kaffirs.

The old days.

I remember Pietermaritzburg’s barking briefings, Kaapstad’s jokes, Kimberley’s religious dogma, East London’s short-lived advice, and Knysna’s naivete. I remember my conscription, my diligent training, the awakening of my bloodlust, my belief and faith—my soldierly qualities. My reassignment: “South West Africa—you’re the kind of man we need up there.” I remember being told I was a closed file already, a corpse that would never be claimed. “Nobody is supposed to know we have covert units there.”

I remember meeting the others. “We’ll call you Johannesburg,” Pietermaritzburg said, “save the other details for a pretty date.”

Kaapstad laughed at my introduction, formal, with a sharp paper cut of a salute. “Do you know what we do in this unit, Joburg?” he asked.

Counterinsurgency: monitoring, tracking, and reporting.

They laughed.

“Not all wrong,” Pietermaritzburg said. “We observe the kaffirs. We monitor the kaffirs. We track the kaffirs. But we’re not David Livingstone or Henry Morton Stanley—we don’t record the lives of kaffirs, Joburg. We end them. Do you understand?” I said I did. “We shall see.” Pietermaritzburg winked at Kaapstad. “How is your military alphabet?” Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo—I was cut off by more laughing and hooting. “It’s shit.” Pietermaritzburg smiled. “Don’t worry, we’ll help you improve it. The first thing you need to know is this: G is for gift. We have a welcoming present for you. Follow me.”

The good old days.

Just days to me.

Old, old days.

ANGOLA

as in Republic of; as in República de Angola and Repubilika ya Ngola; as in “one of the kaffir countries playacting independence,” Kimberley said, by way of welcome, “your new home”; as in mottled shades of green and a silence not found in nature—not even in the desert; as in “Keep your eyes open because the kaffirs are out there,” Pietermaritzburg said, always wary, giving everything two and then three pass-overs with his eyes. “This whole country is camouflage—it puts on its best colors just for you and dulls your senses with nature while it hides the kaffirs. Stay alert, Joburg”; as in ambush, with bullets spraying from anonymous clumps of bush; as in “Step exactly where João steps because these fucking kaffirs have mined the whole place,” East London instructed, “you don’t want to stray off the path and—”

or, apartheid—as in racial segregation; as in God’s Law; as in “God made white people and put them in Europe. Then He made kaffirs and put them in Africa. The yellow Chinaman He put in Asia. And the red people He put in America. Think about it,” Kimberley said, certain, “putting them all on separate continents was a sign the races were never intended to mix. We only came to Africa to manage the bloody kaffirs because they couldn’t do it by themselves!”

BANTU

as in the Ntu peoples; as in migration from West and Central Africa heading south; as in “They’re not even from here originally,” Kaapstad said, laughing at the incredulity of land claims while we were on the march.

or, Benguela—as in oceanic current; as in the poes kou water in Swakopmund or the lonely Skeleton Coast when I visited recently; as in the city by the sea where the kaffirs put some wild blood in the Portuguese women over there; as in Eriel Leila Dos Santos, who said she’d take care of it by herself if she had to, not knowing she’d have to; as in “She’s just another woman,” Kaapstad counseled. “Beautiful, but still a half-kaffir. That child’s going to be whiter than her—that’s an improvement in her general fortunes, I think.”

or, bushman—as in San; as in desert pygmy; as in “The best trackers alive,” Pietermaritzburg said, remembering one who’d served with him. “He could smell which direction kaffirs farted from a kilometer away and tell you their tribe just by looking at their shit. Decent guy”; as in “What happened to him?” asked Knysna, always curious; as in “Had to put him down after he got drunk on the job and nearly got us ambushed. Once you get alcohol in these kaffirs they’re pretty useless. But that boesman was a hell of a tracker.”

CASSINGA

as in Operation Reindeer; as in there is no difference between civilians and soldiers when it comes to the kaffirs: “There are only targets and all that matters is whether they’re moving or still,” Pietermaritzburg said when the news reached us.

or, Che—as in Ernesto Guevara; as in the Argentine Karlo-Marlo terrorist; as in “the Communist Jesus Christ whose lies the kaffirs have ingested whole,” Kimberley said.

or, colonialism—as in the Scramble for Africa; as in “the best thing to ever happen to the kaffirs and the last time anything civil ever happened on the whole bloody continent,” Kimberley added, older, sipping his beer, raising his voice in the bar, certain of securing agreement from the other patronage; as in “Th ese kaffirs complain too much. Didn’t we bring them roads, schools, advanced medicine, and electricity?” he added to vociferous cheering from everyone else.

DE BEERS

as in the diamond company; as in a draft dodger: “Do you know where diamonds from South Africa wind up?” Kaapstad asked. “Somewhere else!”; as in “Then why am I still here?” Kimberley asked; as in “Because you’re not a diamond,” Kaapstad replied, “you’re a doos!”

ENGLISH

as in “The fokken souties who took this country from us,” Kimberley said; as in “Everyone who discovered tea and crumpet roots and fled to that miserable little island to escape the draft,” Pietermaritzburg added.

or, East London; as in never really knew him before he died; as in “The army always has vacancies,” Kaapstad said later that night, eyes dark with hatred after shooting João (“He should’ve known better!” he shouted after Pietermaritzburg asked him why he’d killed our guide), “job openings that need to be filled by soon-to-be dead men. You, Joburg, do you know what we call a pension in the army? A general.”

FIDEL

as in Alejandro Castro Ruz; as in the Communist Godfather; as in the Cuban kaffir who flooded Angola with soldiers we had to work hard to avoid; as in “The fucker outlasted ten presidents, eh,” Pietermaritzburg chuckled, aging, cancer shooting through him. “Maybe there’s something in that Communism shit, eh?”

GIFT

as in the first kill; as in “Right, as you can see, we’re a small unit. We don’t have the resources to keep prisoners,” Pietermaritzburg said. “This one here says he isn’t a PLAN soldier but I don’t believe him. And because I don’t believe him it means he’s lying. I don’t like liars, especially kaffir liars. You see this knife? You’re going to fetch me his eyes, tongue, and ears. If you don’t do it, I will shoot you. You die in real life just like you died on paper when you joined my command. Understand?”; as in I understood very well.

HAVANA

as in Cuba; as in the capital city of Communism; as in “the first gate to Hell,” Kimberley said, “the safest thing to do is blow that whole island up.”

or, Hendrik—as in Kaptein Witbooi; as in “Why you shouldn’t teach the kaffirs how to use a rifle,” Pietermaritzburg said, angry, looking at Malmesbury—another short-lived member of our unit—lying prone, bullet hole through his head after we’d flanked the lost PLAN unit and destroyed it completely.

INSPIRATION

as in electrical shock; as in castration; as in hanging; as in firing squad; as in “Giving the kaffir a reason to answer questions forthrightly,” Pietermaritzburg said, looking at Knysna’s wide eyes when he realized why the captured men were drawing lots. “The one with the short stick gets the long end of the rifle.”

or, interview—as in interrogation; as in when kaffirs are given the opportunity to answer questions forthrightly “as best as they can to see if they get a job among the living or the dead,” Kaapstad said, laughing.

JOCK

as in of the Bushveld by Sir Percy FitzPatrick; as in “I named him after the one in the book,” Kimberley said, lovingly petting his Staffordshire bull terrier when I visited him at his seaside cottage overlooking the Indian Ocean—“I never want to see anything the Atlantic touches ever again,” he’d said earlier in a moment of reminiscence, hands gripping the armrest of his chair.

or, Johannesburg—as in the city of gold; as in home; as in me when Pietermaritzburg phones me and says, “No doubt you’ve heard about what Knysna is trying to do. Well, we’ve got to stop him. Just like the good old days, eh?”; as in another long trip far from home.

KAFFIR

as in aapie, blackie, darkie, bobbejaan; as in the Bantu; as in “all the hard-heeled motherfuckers we fought against to get this land,” Kimberley said, taking aim; as in “Ten rands that kaffir makes it to the tree line,” Pietermaritzburg wagered, gauging the distance, knowing Kimberley was not a good shot; as in “You hit him clean in the brains!” Kaapstad exclaimed; as in “Kaffirs don’t have brains,” Kimberley replied, “just spaces between their ears where we put our judgment.”

or, Kaapstad—as in the comedian from Cape Town; “He’s a soutie, but a good one,” Pietermaritzburg said by way of introduction; as in the best shooter in the unit; as in killed in action in Owamboland; as in “Leave him,” Pietermaritzburg shouted, running toward some rocks for shelter, with gunfire sniffing at our heels; as in “Poor bastard,” Kimberley said, wiping his eyes, taking a sip of his whiskey in the bar, “he could always make a joke. Gave those kaffirs real hell up there!”

or, Kimberley—as in the Big Holy; as in “beloved father, brother, uncle, son, and soldier”; as in died of diabetic complications; as in survived by his widow, his son, my godson of military age, and his daughter; as in “I understand why Knysna felt the way he did, and why he pursued that course of action, but I’m not sure what happened next was correct, Joburg,” he said, years later, looking out at the waves tumbling over themselves in their glee. “I’m not going to shy away from my part in it, but I’m not sure we did the right thing”; as in “Diabetes? That’s a kak way to go, eh,” Pietermaritzburg said, drunk, emotional, scared of the mutiny in his own body. “Imagine surviving Suid-Wes only to be killed by fucking sugar. I’m telling you, it’s not right for soldiers like us to die from civilian causes. Let me face all the kaffirs in the world again, but cancer—”

or, Knysna—as in a boy in a man’s body trapped in a devil’s war; as in the youngest member of our unit, sent to East London; as in the one who always asked if there was no other way; as in “No, there’s no other way, Knysna,” Pietermaritzburg said. “This is the only way in this unit. Now, you either open your gift or I take this knife and unwrap you. Do you understand?”; as in the one who had the worst disease civilian life could conjure up, worse than cancer: the conscience; as in a resort town on the Garden Route; as in a hotel room; as in a restaurant near the marina where we shared drinks—me, Pietermaritzburg, Kimberley, and Knysna, with tense, forced-out laughter, and furtive looks to the left and to the right; as in “Remember the good old days?” Pietermaritzburg asked; as in “There were no good old days,” Knysna replied, “just days, and our evil part in them”; as in “Stop that kind of talk,” Pietermaritzburg said, “it’s the kind of talk that could get you into serious trouble”; as in “Is that why you’re here?” Knysna asked; as in “No, Knysna, we’re just on holiday,” Pietermaritzburg replied, “just a short trip to visit an old friend.”

LUSAKA

as in the capital city of Zambia, formerly Northern Rhodesia; as in the Lusaka Accords; as in the signed lies of ceasefire Castro laughed at; as in the useless pieces of paper that had no hope of ending the Border War.

MANDATE

as in granted to the Union of South Africa by the League of Nations after the Germans lost the First World War; as in administration, not annexation; as in “There was no way the kaffirs could form their own republic,” East London, who considered himself to be a keen political mind, said, “so of course we had to take it over and run it as another province.”

or, menopause—as in a ceasefire; as in a temporary pause on the bloodletting during the Lusaka Accords

or, missionary—as in to lie flat on the ground when under fire.

NAMIBIA

as in the Republic of; as in the former South West Africa; as in the country born from the South African Border War—an illegitimate child of the Cold War; as in the place where military-age males were required to serve; as in the land of savannas, sunsets, the Fish River Canyon, Sossusvlei and its red sand dunes that look like they lapped up all the blood spilled in birthing the country, and the Skeleton Coast in the oldest desert in the world, where the ghosts of dead freedom fighters lurk, whisper, and cry; as in I visited it last year, retracing my steps in a country born from guerrilla warfare and Communism, now a capitalist utopia like the very best of the fallen Soviet and Cuban disciples.

OWAMBOLAND

as in Northern Namibia; as in the blanket and all-encompassing heat; as in the land of the most populous kaffirs in South West Africa; as in entire villages stripped of men and run by women; as in dry patches of sand that turn into miniature lakes in the rainy season.

PIETERMARITZBURG

as in unit leader; as in another “beloved father, brother, uncle, son, and soldier”—I used the same monikers from Kimberley’s funeral since I couldn’t think of anything else to say about the man; as in survived by his daughters; as in “That’s the coldest kaffir-killing bastard around,” Kaapstad told me after my gift was unwrapped, “an odd sort, a soldier’s soldier—you stick with him and you’ll be okay”; as in the man who saved me from certain death countless times; as in the man who could not be reasoned with; as in “Listen, Joburg,” he said over the phone, angry, “Knysna’s conscience has declared itself to be our enemy. Finish en klaar. I’ll see you in the morning.”

or, PLAN—as in People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (formerly SWALA); as in the military wing of SWAPO; as in saboteurs and guerrillas; as in “the nearly invisible monkeys that cannot come out and fight like men,” Pietermaritzburg said; as in the kaffirs who received material assistance from the Communist republics of the world; as in “the devil’s foot soldiers,” Kimberley said. “These devils will fight tooth and nail for this patch of sand beyond reason and hope. They’re up against a superior enemy, but still they fight—if that’s not kaffir black magic I don’t know what is.”

QUININE

as in antimalarial drug; as in “I can’t think of other things beginning with q,” Kaapstad said; as in “That’s a hard one,” Pietermaritzburg agreed, scanning the landscape, stopping the day’s march and bringing a pause to our game of military alphabet. “We stop here for the night. Looks quiet—there’s one for you, Kaapstad: quiet.”

ROOIBOS

as in tea from the red bush, as in a sunset in the south when summer is at its peak; as in “a virgin girl,” Kaapstad said, “because after twelve it’s teatime. What? You’ve never had yourself some rooibos? You should try it. Calms the nerves, it does.”

or, Robert—as in Mangaliso Sobukwe; as in the founder of the Pan Africanist Congress; as in one of the few kaffirs who knew the only way for the kaffirs to fight against his inevitable fate—past, present, and future—was together; as in solitary confinement; as in “You know,” Pietermaritzburg said, fighting a new domestic war, struggling to settle into a life without combat, “I’ve been reading some of the writings and ideas from all the kaffirs on Robben Island. Dangerous stuff , I tell you. If all the kaffirs woke up to such things this damned continent would be quite different”; as in “Isolate the kaffir and the kaffir can’t spread their lies,” Kimberley replied, changing gears, driving toward Knysna’s house, “or our truth.”

SWAPO

as in South West Africa People’s Organisation, as in the former OPO—Owambo People’s Organisation; as in led by Samuel Shafishuna Nujoma—“The Bobbejaan Koning,” Pietermaritzburg said, “you take that kaffir out and you cut off the head of the snake!”; as in “Give it time,” Kimberley said, “all that socialism bullshit he’s preaching is light cologne. It can’t work in that heat. Eventually, the capitalist sweat of the kaffirs will come through.”

TANZANIA

as in the United Republic of; as in Dar es Salaam, the halfway home for SWAPO exiles; as in “the training grounds for many of these damned terrorists!” Pietermaritzburg raged one night, flea-bitten, ragged from the march, low on rations. “I don’t understand why we don’t just wipe out the whole damn lot, from the Cape to Cairo, and be done with these kaffirs once and for all.”

or, transition—as in the strange state between war and civilian life filled with alcohol, nights of sweat-soaked sleep thinking of the ghosts of kaffirs and knowing the war was justified, and “A soldier serves, he doesn’t ask questions,” Kimberley said, gazing at the sea once more, “we did what we had to do”; as in the years spent learning how to shake hands with kaffirs, learning how to be employed by them, how to sit next to them in church and smile and offer them the sign of peace.

or, truth—as in Reconciliation Commission; as in Knysna wanted to appear, testify, and ask for forgiveness; as in “To get amnesty you’d have to tell the whole truth, Knysna,” Pietermaritzburg said, “and many people would be implicated”; as in “The truth will out,” Knysna said; as in “Yes, but not from you,” Pietermaritzburg replied; as in “What happened to brotherhood? We kill our own now?” Knysna asked; as in “You are the last mission,” Pietermaritzburg replied, picking up the gun; as in the truth shall set you free; as in “A man is a poor vessel for secrets,” Knysna said once, hollow, after we’d finished inspiring and interrogating some kaffirs we’d captured—it took the whole day, “we weren’t made to live with lies”; as in spending time compiling important terminology for military-age males, or a truthful account of the old days—still a work in progress, but one step toward the truth in some small way.

UNITA

as in National Union for the Total Independence of Angola; as in the Angolan kaffirs we are bound to help as an excuse to continue fighting the South West African kaffirs.

VASBYT

as in perseverance, as in “Hang in there, Joburg,” Pietermaritzburg said, staunching the wound, “it’s just a scratch. Hold on. Vasbyt.”

WEATHER

as in vane; as in “How do you figure out the direction of the wind?” Kaapstad asked; as in “Simple,” Kimberley replied, “you round up some kaffirs and ask them where their PLAN relatives are”; as in “Then you get some rope,” Pietermaritzburg enjoined, “and find a good tree and rope the whole lot and use the direction of the swaying to figure out whether it’s a southwesterly.”

XHOSA

as in tribe; as in Maqoma, a chief of the kaffirs; as in raider and torcher of homesteads; as in “Round up all the kaffirs and send them to Robben Island is what I say. And drown the remainder,” Kimberley said.

YES, BAAS!

as in “the only good words to come out of a kaffir’s mouth,” Kimberley said, swatting at bugs, loaded down with equipment; “I think heaven is a place where all you hear is Yes, baas! all the time.”

ZULU

as in Shaka; as in killed by Dingane and Mhlangana—“The kaffirs don’t even have basic brotherhood,” Pietermaritzburg said. “But not here, Joburg. Here we’re brothers. It’s the only way we’ll make it through this. Do you understand? You do what I tell you, follow instructions, and maybe, just maybe, you might make it out alive. There will be no songs about us. No medals. So forget all that glory shit. All we have is each other and our targets. We take out our targets before they take us out. Understand? Good. Pass me my knife—you did an outstanding job with unwrapping your gift—neat, no fuss. Now you’ve started on a proper military alphabet. Time to get going on your ABCs.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Only Stars Know the Meaning of Space by Rémy Ngamije. Copyright © by Rémy Ngamije. Reprinted by permission of Scout Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Audio excerpt courtesy of Simon & Schuster Audio from the audiobookOnly Stars Know the Meaning of Space by Rémy Ngamije and read by Janina Edwards, Aaron Goodson, Dennis Kleinman and Anthony Oseyemi. Published by Simon & Schuster Audio, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Used with permission from Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2024 by Rémy Ngamije.