When I glanced out a window and noticed that the sky was turning dark outside, I poked Maurice and told him to gather up his things. I carried the well-loved hardcover of Little Women to the library circulation desk, Maurice following behind holding on to Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day.

Article continues after advertisement

The librarian was kind and familiar with our round, brown faces. She gently reminded us to treat our borrowed books with care.

*

June Jordan wrote,

It seems obvious that the best way to bring people into the library is to bring them in: Bring them in as writers, as thinkers, as readers. I think of the library as a sanctuary from the spectacle, from the alienation, from the unnamed, and the seeming unnameable. A library is where you keep records of involvement, the glorious and ugly tangling of the human spirit with what we meet, what we see. A library is where you keep records of human experience humanly defined: That means humanly evaluated and that means life worded into ideas living people can use. People belong in such a sanctuary. Bring them in. Bring the children into the library as writers; that will help them to think, and that will lead them to read.

Whenever we stepped out of the bright, air-conditioned library into the hazy, twilight heat of the street, I felt an inevitable sense of dread. We were leaving our safe haven, our very own sanctuary.

My mother worked long shifts as a nurse—three to eleven, most nights—so it was usually up to me to make sure that Maurice and I made it home, did our homework, had dinner, and put ourselves to bed. Leaving the library meant stepping into the reality of responsibility and taking care of other people along with myself.

June Jordan wrote, “it seems obvious that the best way to bring people into the library is to bring them in: Bring them in as writers, as thinkers, as readers.”

I hated the fact that Mom had to work so much. I wanted her to be there to make us dinner and greet us when we got home. I didn’t like fending for ourselves, but I also didn’t like to be alone with my mother’s boyfriend.

We climbed up the hill to our house, our backpacks weighed down with our library books, and came home to our empty apartment. I turned on lights, and cooked something that smelled good, and reminded Maurice to take a bath and brush his teeth. I did my best to make things warm and safe and snug.

Then, after we changed into our night clothes, we climbed into our little beds, and I read to him first, all about Alexander’s disaster of a day, until I heard his breath go slow and steady and looked to see that his eyes had fallen shut. Then I opened my copy of Little Women and picked up where I had left off.

*

My mother made a friend in our new apartment building, a woman named Elizabeth Woldemichael who lived in apartment 7 to our apartment 5, both of us on the third floor. Ms. Woldemichael had emigrated from Eritrea, in East Africa, around the same time my mother had come to the United States from Nigeria. She was a single mom with twin girls, Ida and Selma.

“You should be friends with them,” said my mother. “They’re just your age and such nice girls. So smart and polite!”

My mother was hovering in my bedroom door as I was reading Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry and doing my best to ignore her. If I couldn’t be at the library, this was the next best place, lying on my bed, propped up on my elbows, reading, preferably with the door shut.

“Glory? Are you listening? These girls live only two doors down. You’re lucky to have them so close. If you get to know them now, you will have nice friends at your new school when you start in the fall.”

I rolled my eyes. I didn’t want new friends. I was still grieving Charisse and all the friends I had left behind at my old school. What was the point of bringing new people into your life if they were only going to leave anyway?

My mother badgered me all summer, but I was resolute in ignoring her. Whenever I happened to pass the sisters in our hallway or outside the building, I would pointedly look away.

Instead, I haunted the library, and if I couldn’t be there, I stayed in my room and read, doing my best to block out the noise of my mother and her new husband arguing over… everything, really.

*

Because I still harbored fantasies of my parents reuniting, of my father returning from Nigeria and making it all better, I would not have been happy even if my mother had chosen a good man to be with. But this was not a good man. Even as a young, snarky teen, I could tell, this was bad.

His rigidness plagued our household. There was always a sense of agitation— jeering glances and constant disapproval.

My body tensed as he creeped outside of my bedroom door. The emotional abuse was always present but harder to define at the time. He demanded to be in control of my mother.

All I could do was watch helplessly. I was too shielded and inexperienced to understand things like bills or green cards or any of the many reasons a woman might think she needed a man in the house at any cost. I just knew that our new home was not a safe space and that my mother’s marriage was not going to be a happy or nurturing relationship.

I could tell that something essential was being forced. That there was oppression and danger in our house.

But, of course, I was not allowed to voice this fear.

*

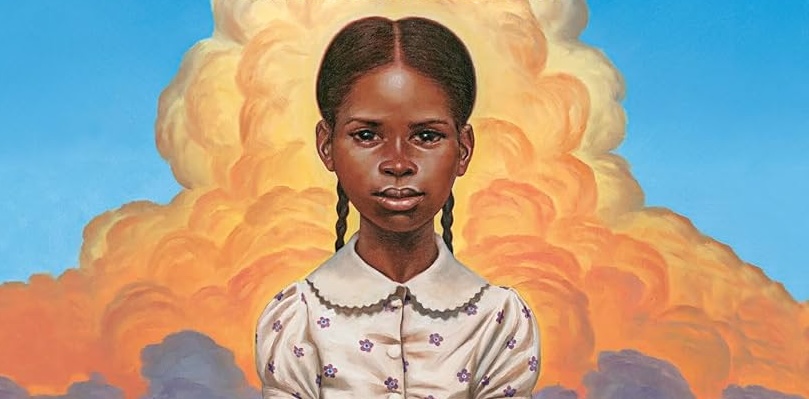

Other than Little Women, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was the book I loved best that summer. The novel, written by Mildred D. Taylor, is set in Mississippi during the Great Depression, against a backdrop of racial tension and segregation in the American South. At ten years old, Cassie is a strong and determined character, especially considering the challenges she faces in a white-dominated world.

I immediately recognized and admired her outspoken nature and self-confidence. Despite their obvious differences, Cassie Logan and Jo March felt essentially the same to me. They were both strong, outspoken girls who cared for their siblings. They made mistakes, but they kept their integrity, no matter what they were faced with.

I recognized them both. They spoke to me, right from the page, and as far as I was concerned, they were all the friends I needed.

I liked that Cassie was Black, and I recognized and responded to the Black pride that filled that particular story. But unlike many of the Black women who later joined the Well-Read Black Girl Book Club, I hadn’t really been craving that reflection of myself in the books I read. Arlington in the early 1990s was a hub for immigrants and very multicultural. I was lucky to be surrounded by Black people. I never found myself in spaces that were dominated by white people.

I never felt different or alone in that way. I wasn’t searching out these books to see myself reflected because I was already surrounded by people who looked like me. I didn’t need that kind of shoring up.

What I was truly interested in were stories of children who were in peril and somehow made it out. I needed to read to understand survival. I wanted to know how you developed character, how to face adversity and overcome it and still come out as an intact person. I wasn’t looking for a reflection; I was looking for practical advice. I liked Hatchet because it read almost like an instructional pamphlet on how to survive in the wilderness.

After reading that book, I truly felt that I could make it on my own if I ever crashed into a remote Canadian forest. I liked Little Women and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry because those girls were struggling, they had burdens and responsibilities beyond their years, and they still found a way to be emotionally fulfilled. They found a way out of the danger that surrounded them.

In fact, the last thing I was looking for in these books was a mirror image. I wasn’t much attracted to who I saw in the looking glass in those days.

After my father left, I began to dismiss the fact that I was Nigerian. My father had always been the one to keep that part of our heritage alive. He had made sure that Maurice and I knew exactly where we were from and who we were. He had taught me to be proud to be Nigerian.

But now, with him so suddenly and brutally gone, I didn’t want to be African anymore. For all his love of our country, he had spoiled it when he chose Nigeria over me and Maurice. I believed he had rejected me, so I began to reject what had been most essential about him. To wish myself into a new, non-African version of Glory.

I liked the idea of Cassie’s southern American Blackness. It felt like a culture I could aspire to, and so much easier to explain than being from Nigeria. I liked the fact that her family owned and valued their land above almost anything.

The description of their physical home and the landscape around it spoke to the part of me that had been uprooted over and over, the little girl who saw her things scattered across the lawn and into the street.

The description of their physical home and the landscape around it spoke to the part of me that had been uprooted over and over, the little girl who saw her things scattered across the lawn and into the street. I wanted a real home.

I longed to own something that couldn’t be taken away. A place where people stayed put. And this idea gave me something to look forward to, an image to move toward, the possibility of what would come if I could just find a way to navigate through those hard times.

______________________________

Excerpted from Gather Me by Glory Edim. Copyright © 2024 by Glory Edim. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.