In the autumn of 1954, Minnie Mae, who was 21 years old, became sick with a blood-related cancer, as did several others in the small farming community in South Dakota where she lived. She spent Thanksgiving with her family but was hospitalized by Christmas. She died on January 11, 1955, leaving behind a one-year-old son, a three-year-old daughter, and an extended family shaken with grief.

Article continues after advertisement

Minnie was my grandmother. I grew up with the story that she was killed by nuclear radiation poisoning. The summer before she became sick, red dust allegedly blanketed the prairie in the valley where she lived. For three days, people wiped this dust off their windshields and removed their linens from clotheslines. Soon afterward, the diagnoses began. Two people from neighboring farms died of quickly progressing cancers shortly after Minnie died. A nine-year-old girl developed a brain tumor.

In addition to being Minnie’s granddaughter, I am an anthropologist who studies how people make sense of science. Over the past year, I have turned my expertise toward my own family, investigating the rumor of fallout in Minnie’s community. In my research, I’ve learned that some details of the story of nuclear fallout do not add up. The US government did not conduct atmospheric nuclear tests in the continental US in 1954 that would link red dust to atomic fallout. The common cancers caused by radiation usually develop over many years, not over a period of weeks.

That these rumors exist is evidence that we are living with fallout of a different kind: the widespread social fallout of government deception.

Still, the more I learn, the more the story makes a certain kind of sense. The US conducted hundreds of nuclear tests in the 1950s—the largest of which was carried out in the Marshall Islands in the spring of 1954. Because of miscalculations, the test was at least twice as large as researchers had planned, its enormous mushroom plume poisoning the surrounding islands and sending radioactive dust traveling thousands of miles away.

Even though the nuclear testing in the Pacific was far from South Dakota, the state’s primary daily newspaper, the Argus Leader, reported that so many people were expressing concern about fallout that the governor wrote to the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss. Strauss replied that they were monitoring radiation levels, and the amount of fallout was small—no cause for concern. The exchange ran in the Argus Leader, on June 14, 1954, not long before Minnie became sick.

The week after Minnie’s funeral, the newspaper ran a two-page feature downplaying fears of nuclear radiation. It proclaimed that “fallout has not affected the general health of the American people. It does not cause epidemics of known diseases, nor does it cause new, different, or mysterious diseases.” It reported in bold: “Even Close Up, You’re Safe” and “Policy-Makers Aren’t Worried.” The article sought to calm the public by reassuring them that scientists knew “exactly what they were doing.”

Two weeks later, the US government-initiated Operation Teapot, exploding fourteen nuclear bombs in Nevada that spread radiation across the US over the next five months.

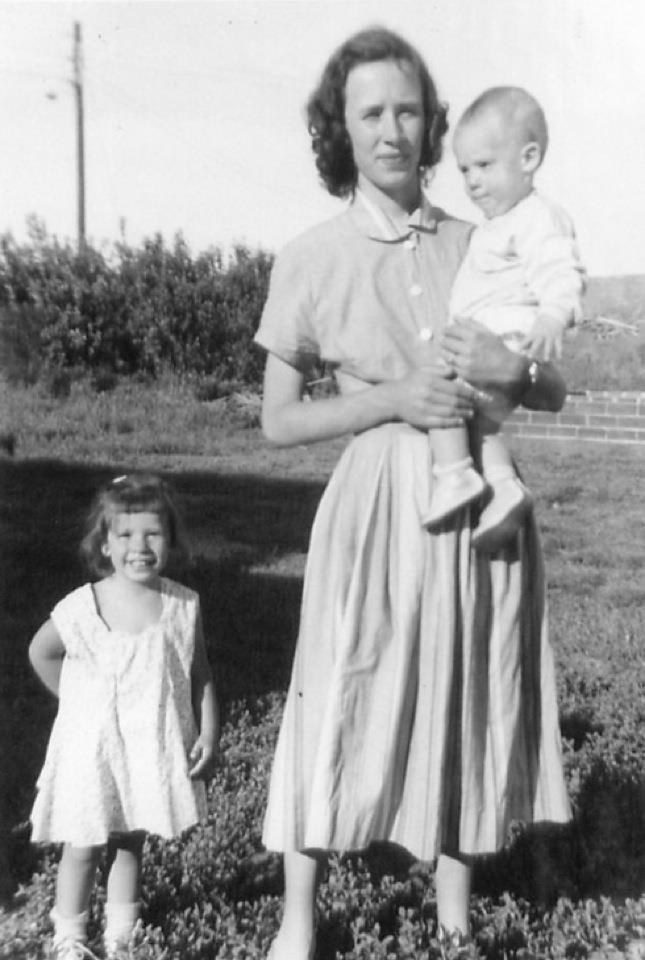

Minnie in the South Dakota prairie.

Officially, people in the US were safe, but unofficially illness was spreading. By the mid-1950s, it was becoming clear that atomic testing was far more harmful than policy makers let on. My dad’s family is full of scientists and engineers—not the sort of people to give weight to conspiracy theories and rumors. But they lived in a prairie town with fewer than 150 people and several residents developed cancer at the same time, just as the US nuclear energy program was ramping up.

Soon afterward some scientists in South Dakota began to carry Geiger counters. As reported in 1988 by investigative journalist Patrick Springer, after a heavy rainstorm in South Dakota that followed atomic testing in Nevada in 1957, a professor from the South Dakota School of Mines named John Willard registered radiation levels that were 2,500 times higher than usual in a puddle of rainwater. Willard alerted Civil Defense officials, washed down streets where children were playing, and recommended that hay and milk be dumped. Officials challenged his readings and scolded him for unnecessarily worrying the public.

But it was becoming increasingly clear that the official story could not be trusted. People began to suspect that the US government was spreading disinformation about the safety of nuclear testing. In the case of my family, I can understand why they would have turned to their memories of red dust to make sense of Minnie’s death.

I have come to doubt that three days of fallout in the summer of 1954 killed my grandmother. The timeline of the nuclear testing and the pace of cancer in her community just don’t fit. But since I started investigating Minnie’s death, several people from the Midwest—all of whom grew up outside of known nuclear hotspots—have reached out to me with similar rumors: wilted flowers covered in strange residue, unexplained rashes, a cow that birthed five calves, vacant lots rumored to be storing nuclear waste, pink snow.

That these rumors exist is evidence that we are living with fallout of a different kind: the widespread social fallout of government deception. For many years, officials dismissed legitimate fears, lying to their constituents so the US could expand its nuclear arsenal. I grew up with Minnie’s death as a cautionary tale that the US government will harm the people it claims to defend. My dad fled the continental US for Alaska when he was the age that his mother was when she died. His reasons for leaving are complex, but he was clear in his longing to get away—to live off the grid. Much of my childhood was spent on a remote island homestead where we did not depend on public services and paid no local taxes. My story is unique, but I am not alone in being raised to distrust my government.

At the end of the 1950s, as the dangers of nuclear testing became impossible to hide, people across the country and across political divides began to protest the dangers associated with nuclear weapons programs. In the first opinion piece ever published in Playboy Magazine, in 1959, the editors argued that nuclear testing was enabled by “a conspiracy of silence” and that it was time to sound alarms: “Fallout penetrates our water, our soil, our milk, and our other foods. Eventually it penetrates our bones and can cause leukemia. It can lodge in our reproductive organs causing sterility or mutations—malformed births,” the editors wrote. They acknowledged this was an unusual message to come from an adult magazine, but cautioned there would be no fun and pleasure if “life itself ceases to exist.”

People and politicians both listened—not just to Playboy’s editorial, of course, but to the tens of thousands of people, journalists, Indigenous activists, and scientists across the US who were beginning to speak out. The last atmospheric test was detonated by the US government in 1962. The next year, the US banned atmospheric testing, and after several more years of protest and activism, in 1968, the US signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, slowing the frenzied pace of nuclear weapons development. Underground testing of nuclear weapons continued until 1992, but in my lifetime, the US government has undertaken no atmospheric tests.

Still, we continue to suffer from the social fallout of widespread distrust in our public institutions. Atomic testing did not only poison our water, soil, milk, and food. The secrecy and deception surrounding the nuclear weapons program also poisoned the relationship between people and government, replacing it with justifiable suspicion and doubt. According to the Pew Research Center, trust in the US government began to drop precipitously in the mid 1960s and it has never recovered.

Today, nuclear technologies are back in the news. The military has begun investing trillions of dollars to replace an aging nuclear arsenal. Corporations are ramping up production of nuclear plants to power rapacious AI data centers. Expanding markets for uranium risk spreading cancerous hazards across the earth. While President-elect Donald Trump was on the campaign trail, his advisers proposed reviving a US nuclear weapons testing program.

The challenge in front of us is to learn how to be critical of our public institutions, without relinquishing hope that these institutions can become less harmful than they were in the past.

To protect our health against radioactive fallout, we will need careful oversight, regulation, and meticulous safety standards. To protect our communities against social fallout, we will need transparency, accountability, and expanded public education to help us discern disinformation from facts. In short: nuclear expansion calls for a concomitant funding of public services.

The real-life Catch 22, here, is that a stronger government will be hard to stomach given past deceit. When I talk with people about nuclear history, I encounter widespread skepticism that politicians and scientists who misled us in the past will be honest with us today. Many have no faith that the government will care for them.

Having grown up with the story that fallout killed my young grandmother, I relate deeply to this skepticism. But widespread public distrust can be as dangerous as red dust. People who do not trust their government may become suspicious of public health programs that would keep them safe. They may also become disengaged with democracy writ large. When it comes to nuclear technologies, those pushing for expansion at all costs would benefit from a disaffected public.

As I have unearthed my grandmother’s past, I have encountered a side of the government not made up of deceptive officials, but of civil servants committed to transparency. State auditors and educators have spent hours digging through files carefully preserved in case someone with questions, like me, comes along. One state-funded librarian, unprompted, sent me a link to a report about the “dust bowl” of 1954—a clue to part of my family’s story. State archivists have helped me locate records of Minnie and her neighbors in newspapers, including an article that describes my infant father and his older sister spending New Year’s Eve in the hospital with their mother, back when they had hope she would live.

State historians as well as National Park Rangers have taught me about how South Dakota played a central, if quiet, role in US nuclear history, pointing me to documents about intensive uranium mining and disposal in the state as well as the construction, in the 1960s, of more than one hundred and fifty nuclear missiles buried throughout the wide open expanse of the prairie. They, too, want to understand the social context that gave rise to the rumors of Minnie’s death.

Minnie with her children after church in the spring of 1954.

Minnie with her children after church in the spring of 1954.

The public agencies that have funded my research require me to clarify in all my work that my views are my own. This separation is largely so they are not held responsible for what I write, but it also means that I can use grants from the US government to critique the US government. When I consider how to repair our communities from the social fallout of past government deception, this freedom of critique is high on the list. The distrust people feel about the harms perpetrated by the US government is real and well-founded and deserves to be treated as such.

The challenge in front of us is to learn how to be critical of our public institutions, without relinquishing hope that these institutions can become less harmful than they were in the past. This present moment of nuclear renewal calls for social uprising and protest—and also civic engagement. Between the 1950s and 1980s there was a concerted movement to reform nuclear power through local activism, but also through official channels of law, science, education, and governance. This effort on all sides kept full-blown nuclear war from breaking out back then—and it can be successful again today.

For my part, I am learning how my grandmother’s tragedy mirrors a larger national legacy of distrust. The stories I’m unearthing in the mystery of the red dust are not only about the untimely death of a young woman who never got to live her life, but about a betrayed nation that has yet to heal.