The opening moments of Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel The Custom of the Country depict the newly moneyed Undine Spragg lounging in the Stentorian, a New York hotel evidently named for its raucous guests. The “highly-varnished” rooms feature “heavy gilt armchairs,” gaudy bric-à-brac, and “salmon-pink” walls on which hang portraits of aristocrats whose excesses ushered them to the guillotine. The overdone Spragg suites echo the “wilderness of pink damask” of the nouveau riche Norma Hatch of Wharton’s 1905 novel The House of Mirth.

Article continues after advertisement

The Spraggs and the Hatches—think: Bertha and George Russell of The Gilded Age—represent the “new people” of The Age of Innocence for whom “conspicuousness passed for distinction.” Theirs is the “gilded age of decoration” indicted in Wharton’s first prose book, The Decoration of Houses (1897), which has been called “the most important” interior design manual “ever written” and the “pioneering guide” to which “all modern design books owe their existence.”

The force behind this book, Edith Newbold Jones Wharton (1862–1937), was one of the most popular, critically acclaimed, and handsomely paid writers of her time. Wharton was the first woman awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (for The Age of Innocence), an honorary Yale doctorate, and full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. With a life bracketed by the Civil War and the rise of Nazism, Wharton saw astonishing social and cultural change in her native country and abroad. The happy consequence of having been compelled by her parents’ finances to relocate as a child to Europe was to relish always “that background of beauty and old-established order.”

It is a wonderful synchronicity that Wharton was distinguishing herself as a homeowner as she was finding her place as a writer. While she would become recognized as a master of fiction with the critically and commercially successful The House of Mirth, The Decoration of Houses put Wharton on the map as an authority on domestic aesthetics at the turn into the century. In the time between the two books, Wharton published widely across genres. Wharton’s establishment of herself as an expert on aesthetics and the art of fiction, with a command of Italian art and culture, is particularly impressive given that she did so, as Laura Rattray has shown, in a climate that frequently sought to undermine, second guess, and pigeonhole her for being a woman.

To wit, an advertisement for the book’s British publication promised a collaboration between “American Lady Artist” and “Architect.” After all, The Age of Innocence, which returns to the 1870s of Wharton’s youth, reminds us that architecture and painting were thought “subjects for men, and chiefly for learned persons who read Ruskin.” Wharton, who claimed Ruskin as a formative influence, would complicate this model with her career as a professional writer.

For Wharton, in philanthropy and creative work, the care of the home is the care of the soul.

The Decoration of Houses, which Wharton wrote with the Beaux-Arts architect and Boston-based interior designer Ogden Codman Jr. (1863–1951), argues for the limitless possibilities afforded by the home’s appropriate design and décor. The treatise makes the case that aesthetically pleasing interiors emerge from sound decorating, emphasizing “those architectural features which are a part of the organism of every house, inside as well as out.” Rooms, the authors argue, should be as beautiful as they are useful—an unpopular sentiment, as indicated by the number of overcrowded and ornately decorated Victorian drawing rooms.

Wharton’s keen sense of the home’s sacredness would propel her to fight on behalf of those displaced by World War I. For the writer who rose to fame with a design manual addressed to the leisure class would be the same who, decades later, would oversee The Book of the Homeless, a collection of original writings and artwork, whose table of contents reads like a who’s who of early twentieth-century artists and intellectuals (Renoir, Sargent, James, Yeats) and whose proceeds were invested in the welfare of war-torn children and refugees. Wharton’s humanitarian acts—e.g., her establishment of homes for tubercular soldiers and their families—for which France awarded her the Legion of Honor and Belgium Chevalier of the Order of Leopold, seem to have been driven by her awareness of the restorative properties of the home. For Wharton, in philanthropy and creative work, the care of the home is the care of the soul.

The Decoration of Houses crystallizes what Wharton and Codman found troubling in American tastes at the turn of the twentieth century and its argument can be summarized in three main points. First, “proportion is the good breeding of architecture” and “the essence of a style lies not in its use of ornament, but in its handling of proportion.” Wharton and Codman advocate European principles of harmony and symmetry, many of which were borne of her time abroad and his having lived in France and traveled Italy. The book emphasizes proportion and design in furniture, ornament, walls, floors, ceilings, doors, and all aspects of domestic architecture. Wharton and Codman were going against the grain which emphasized superficial application of ornament. Although the authors were speaking to late Victorians, their insistence on honoring proportion and limiting the use of ornament is timeless when one considers the awkwardness of an oversized entryway on a small house or a Cape-style home burdened by more holiday decorations than it can sensibly support.

The book’s second point is that returning to the best models of the past can elevate house decoration above its unfortunate status of confusion, decline, and vulgarity. Here Wharton and Codman echo the esteemed New York architect Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead & White whose vision would produce the Boston Public Library, the Morgan Library, and Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus. Third, Wharton and Codman suggest that those aspirational models can be found chiefly in the buildings erected in Italy after the early 1500s, and in France and England, once the full effect of the Italian influence set in.

While it is tempting to glance at the illustrations—a Versailles library here, a Pitti Palace bathroom there—and dismiss The Decoration of Houses as not relevant to us, Wharton and Codman’s advice resonates for the consumer interested in beautifying their domestic space on a sensible budget. Their tips, for instance, on how to frugally furnish a room make sense for the modern-day homeowner or apartment-renter. Wharton and Codman recognize a place for materials that are more affordable than marble or velvet and give space to the challenges of decorating the smaller rooms in which twenty-first-century readers likely dwell.

They discourage the use of dark colors, which “have the disadvantage of making a room look small.” In decorating a room they advise that the color scale ascend gradually from a dark floor to a light ceiling—a tip basic to sound interior design. As a rule, Wharton and Codman suggest that the vulgar and the showy be sacrificed in the name of architectural integrity. This practice clearly speaks to the twenty-first-century decorator interested in clean lines and open, uncluttered spaces.

Wharton and Codman bemoaned America’s lapse from “the golden age of architecture.” An early draft of The Decoration of Houses laments the “hopeless quagmire of vulgarity and wrongness” into which architecture and decoration had wandered. The book frowns upon the conspicuous displays of wealth evident in the overdone hotel suites in The Custom of the Country and the Gilded Age equivalents of the McMansion, many of which were ultimately razed. Wharton and Codman also sought to counter the advice found in two exceedingly popular decorating guides they despised—Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste (1868) and Clarence Cook’s House Beautiful (1877)—dismissing both tomes as sentimental, unscholarly, and unscientific.

Wharton’s collaborator and, at times, kindred spirit, Ogden Codman Jr., had served as an advisor for the decoration and renovation of Land’s End, the newly married Edith and Teddy Wharton’s summer home in Newport. Codman would later design the interior of the Whartons’ Park Avenue residence in New York City. Letters exchanged between the co-authors in the 1890s are often affectionate. She adorably addresses him as “Coddy” while he calls her “the cleverest and best friend I have ever made.” They bonded over a love of architecture, interior design, travel, gardens, dogs, and gossip.

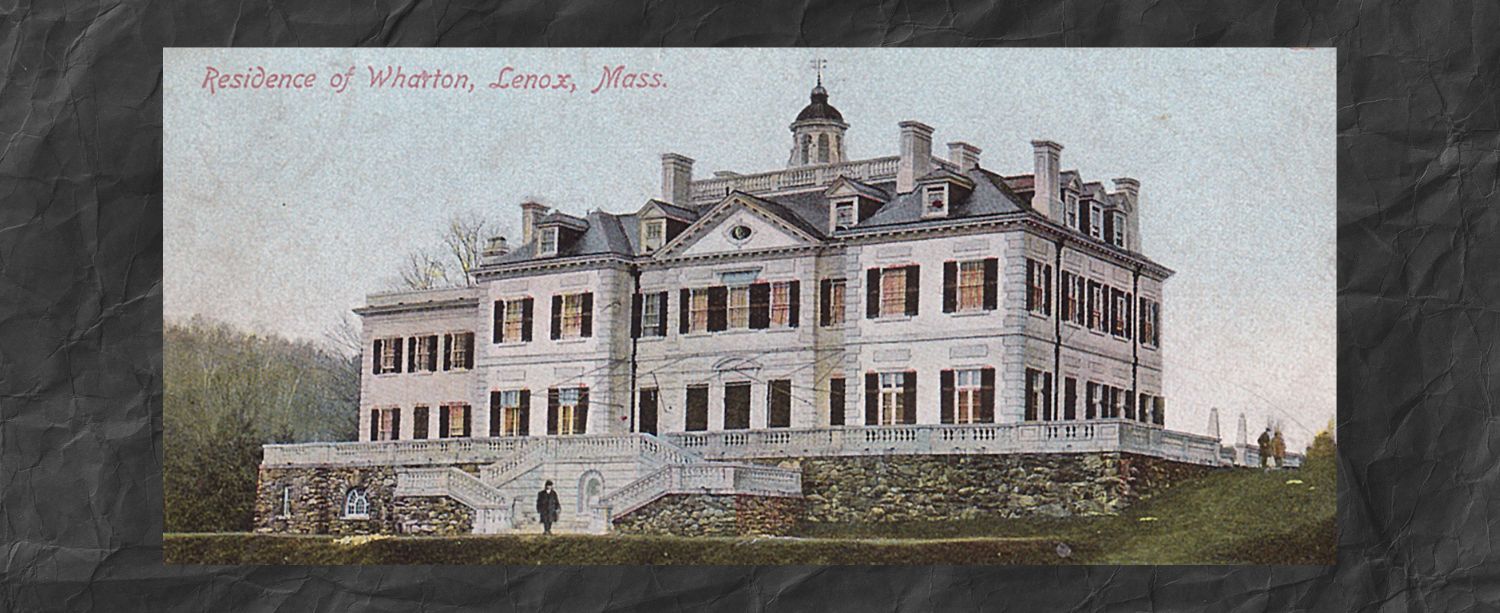

Although Codman consulted with Wharton on the early stages of the design of her exquisite Berkshires home, The Mount, whose construction lasted from 1901 to 1902, he did not, ultimately, serve as architect. As Eleanor Dwight notes, “the two had a falling-out. Codman had raised his rates from fifteen to twenty-five percent, and Teddy refused to pay this fee.” The Whartons turned to Francis Hoppin, who apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White. When the Whartons later sought Codman’s help with The Mount’s interiors, further discord ensued over his fees for the painted panels in Edith’s boudoir and the strain took a significant toll on the friendship.

Main House, Edith Wharton’s home, photography by Christopher Duggan, courtesy of The Mount, Lenox, Massachusetts.

Because of the tensions in Wharton’s collaborations with Codman, architects do not come across well in her writings. Architects with questionable characters and egos as inflated as their prices appear in “The Valley of Childish Things,” Sanctuary, and Summer. Thirty years after The Decoration of Houses, Wharton was working on a novel that was to feature an architect who sounds a lot like her descriptions of Codman: “boastful, a little obtuse, and rather vain.”

Nevertheless, Wharton and Codman’s partnership yielded a beautiful book that has never gone out of style or print. When, in June 1937, the authors were planning a new edition of The Decoration of Houses, Wharton fell ill after arriving at Codman’s French chateau and was carried off in an ambulance. She never regained her health and died in August. It is no small matter that her last recorded words were “I want to go home.” That detail, and the fact that in her final months Wharton was returning to The Decoration of Houses, suggests the central place the book, and the quest to find and make one’s home, occupies in her legacy.

It is no exaggeration to say that Edith Wharton’s philosophy of domestic aesthetics extends further than she could have imagined.

Edith Wharton is arguably the only American writer who taught herself architecture, interior design, art history, and garden planning. Architecture was so important to Wharton that she considered it a “ruling passion” alongside justice, order, dogs, books, flowers, travel, and a good joke. Henry James would affectionately say of Wharton that “no one fully knows our Edith who hasn’t seen her in the act of creating a habitation for herself.” Similarly, readers of Wharton’s celebrated novels, and increasingly appreciated achievements in the short story, poetry, playwriting, travel writing, and memoir, can only become fully acquainted with her by turning to her contributions to the study of architecture and design.

A new edition of The Decoration of Houses from Syracuse University Press is fully annotated for the first time to contextualize Wharton’s richly allusive prose, seeking to enable readers to draw meaningful connections between the design ideas expressed in the 1897 book and Wharton’s strategic use of spaces throughout her writings across genre and class. Wharton’s respect for and command of visual culture and sound design, her insistence on eliminating “bric-à-brac” and cultivating one’s garden, permeate just about everything she wrote. We see it in the penurious heroine of “Mrs. Manstey’s View” who puts her life on the line to protect the view from her boarding-house window.

A similar investment in lovingly curated domestic spaces surfaces in “The Dead Wife,” a haunting poem in which a ghost yearns for a glimpse of the room she decorated to see the extent to which her imprint has been eclipsed by her husband’s new wife. In the equally chilling ghost story “Afterward,” Wharton writes that “the house knew” where and why a husband had vanished, the library in which his wife “spent her long lonely evenings knew.” The well-heeled Newland Archer’s refusal to relinquish his “‘sincere’ Eastlake furniture” shows him to be more old-fashioned than he would care to admit. The “unusually forlorn and stunted” facade of Ethan Frome’s house unsubtly reflects the emotionally and physically bereft state of the eponymous protagonist.

The Connecticut home of Sara Clayburn, described in Wharton’s posthumously published ghost story “All Souls’,” calls to mind Wharton’s own sensibly designed residences and her relation to them: “The house…was open, airy, high-ceilinged, with electricity, central heating and all the modern appliances; and its mistress was—well, very much like her house.” The “horribly poor but very expensive” Lily Bart’s sense that she might “be a better woman” if she had a drawing room to “do over” assumes new meaning when read in the context of The Decoration of Houses. As Elif Armbruster has noted, Lily’s “lack of attachment to a home is the strongest clue to her imminent demise.” Lily is, to borrow a Wharton phrase, “expatriate everywhere.”

View from Edith Wharton’s terrace at Castel Sainte Claire, Hyères, France, 2023, Photography by Nels Pearson.

View from Edith Wharton’s terrace at Castel Sainte Claire, Hyères, France, 2023, Photography by Nels Pearson.

The Decoration of Houses is arguably more useful than ever before in our lifetimes, particularly as a pandemic compelled us to reimagine, and in many cases conduct business from, our homes. More people have adjusted their habits such that the acronym WFH is now part of the modern lexicon. The book’s recommendations for honoring the architectural integrity of our living spaces and introducing more harmony, balance, symmetry, order, simplicity, well-made furniture, lightly colored walls, and the right kind of light are being drawn upon to enhance the quality of our lives. Wharton and Codman’s no-nonsense advice—“good things do not always cost more than bad”; “better to buy each year one superior piece rather than a dozen of middling quality”; avoid the tendency to “buy too many things, or things out of proportion with the rooms for which they are intended”—is as useful to the twenty-first-century shopper as it was to the conspicuous consumer of the American 1890s. After all, Marie Kondo’s call, in The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, to eliminate what fails to “spark joy,” is a modern-day version of Wharton’s insistence on banishing the “ugly,” the “showy,” and the “vulgar.”

Given the considerable attention paid, in our twenty-first-century lives, to the relationship between domestic environments and the wellness and mindfulness of the soul, it is no exaggeration to say that Edith Wharton’s philosophy of domestic aesthetics extends further than she could have imagined. It is the hope that the present volume, each chapter annotated to gloss Wharton’s allusions to art, architecture, design, history, literature, mythology, foreign figures of speech (originally left untranslated from French, Italian, Latin, German, and Greek), and concepts unfamiliar to what the French economist Thomas Piketty has called our “new Gilded Age,” will enable the reader new to, or well versed in, Wharton to fully grasp the extent to which an investment in the poetics of space permeates her entire corpus. At the same time this edition seeks to support all readers in their quests to “bring out the latent graces” of their living spaces and achieve what Wharton in Sanctuary calls “that rare harmony of feeling which levies a tax on every sense.”

__________________________________

From The Decoration of Houses by Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman. Introduction copyright © 2024 by Emily J. Orlando. Available from Syracuse University Press.