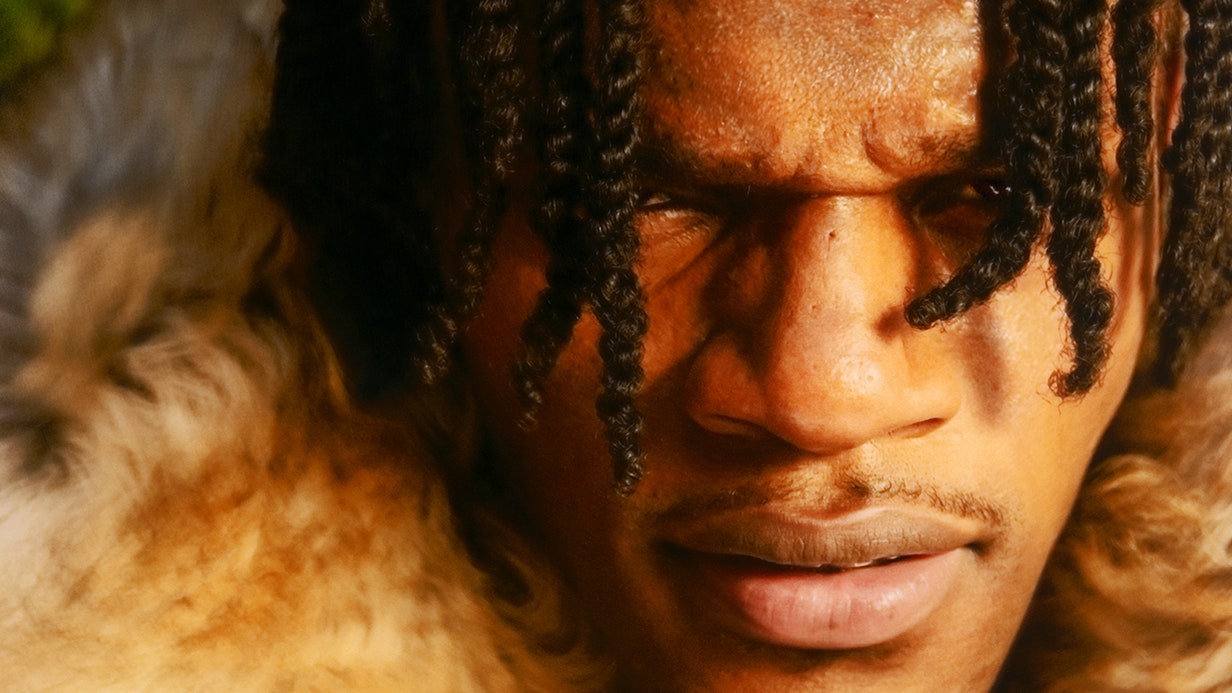

Growing up, Jackson was singularly motivated to reach the NFL, and the financial stability that comes with it. “I knew I wanted to be rich and for my people to be well-off,” he says. “I don’t want to be around chaos.” But he had a silly side, too, and stayed busy playing football. “I was always goofy, but I always talked about football,” he says. “My friends were grown-ass men. We’re 12 and 13, they were already doing shit like the older guys. Hell nah. When my old friends got in trouble and I’d see that they got five years, I’m like, ‘What the fuck? What the hell he did?’ Robbery. I’m like, ‘I don’t want money that bad. I can wait.’”

Florida has a rich history producing some of the NFL’s most electric players: Deion Sanders, Devin Hester, Michael Irvin. Jackson fits seamlessly into that lineage, complete with mythological backstory: His high school team did not have a written playbook, just hand signals denoting what play to run.

Even without the traditional structure that produces so many NFL signal callers, Jackson was beasting on the competition from the very start. “Ever since I started playing, I was like that,” he says. This is, in many ways, the whole deal with Lamar Jackson. Asking him to play like Manning is like buying a Lamborghini and refusing to take it out of first gear. To get the most out of the experience, one must embrace the horsepower. “There are people out there who just need a chance,” Ravens head coach John Harbaugh tells me. “Because they don’t look, feel, talk, say the same things that I’m used to hearing, that doesn’t mean they can’t do the job.”

Still, despite his one-of-one abilities, superstardom has never been a seamless fit for Jackson. Petrino says Jackson loathed certain aspects of the college recruiting process so much that he ultimately committed to Louisville without even visiting. By the way, if you’re questioning how a prospect like Jackson wound up in Kentucky, rather than his hometown University of Miami, the interest, Lamar felt, was not mutual. “Miami was my favorite school,” he says. But the team’s coach seemed uninterested in local talent, to Jackson’s unending frustration. “We’re the ones who made Miami what it was! When they started recruiting everyone else, they was sorry as hell. All the talent, all the real athletes, they were from here. Man, I’m not going there to be ass. That was my favorite school, but I don’t want to be at an ass school.”

While the old guard still prefers quarterbacks to be more war general and less laid-back jokester, Jackson thrives with a loose, unburdened mindset. The more stone-faced and tense everyone around him is, the less he feels like himself. Perhaps his most dominant game in college was the time he put up five touchdowns to topple a Florida State team that had won 53 of its last 59 games. Before that game, Jackson tells me, he was prancing around the locker room wearing an offensive lineman’s cleats. Bullshitting, in his words, and not in the way quarterbacks usually do. The problem with so many modern athletes, he thinks, is simple. “Everybody’s so serious! When you’re too serious, I feel like you’re scared. I’m like, ‘Let’s get it. They can’t fuck with me.’”