For a magazine that’s been around for more than a century, one might suppose that it has had its act together for much of that time. But the truth is: The New Yorker has been restless since its debut in the mid-Roaring Twenties. That restlessness, defined by a desire and openness to change, has been, and continues to be, its core strength.

Article continues after advertisement

The magazine that made a name for itself in the last millennium is in some ways not the magazine it is today. And we hope that The New Yorker of a hundred years from now will not be a duplicate of the current magazine. It has always been the magazine of surprise, beginning with issue #1’s cover by Rea Irvin of an oddly compelling top-hatted Victorian-era gent (soon to be dubbed Eustace Tilley). The magazine’s cartoonists have kept the element of surprise afloat to this very day. Who among us does not flip through the latest issue to see the cartoons, looking and hoping to be surprised.

They remain, for the most part, solo acts, seeing what most of us see, then running that through their brain’s highly attuned and complex cartoonist gadgetry.

My guess is that not a year has gone by—not even a month in a year—without someone somewhere saying that the cartoons “aren’t as funny as they used to be.” If we’re lucky, that will continue as long as there’s a New Yorker. Change at the magazine means that the idea of what’s funny changes. In 2025, cartoonists should not be trying to mimic cartoons that tickled funny bones in 1925—they should be capturing the humor of the present. Looking at a 1920s cartoon will inform you of that era’s fashion and concerns and behaviors, and even politics. The same can be said for the cartoons of the 2020s. Around and around it goes, with plenty enough oddities to make things more than interesting. This is the meat and ‘taters of The New Yorker.

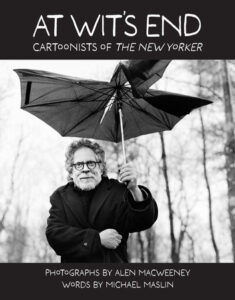

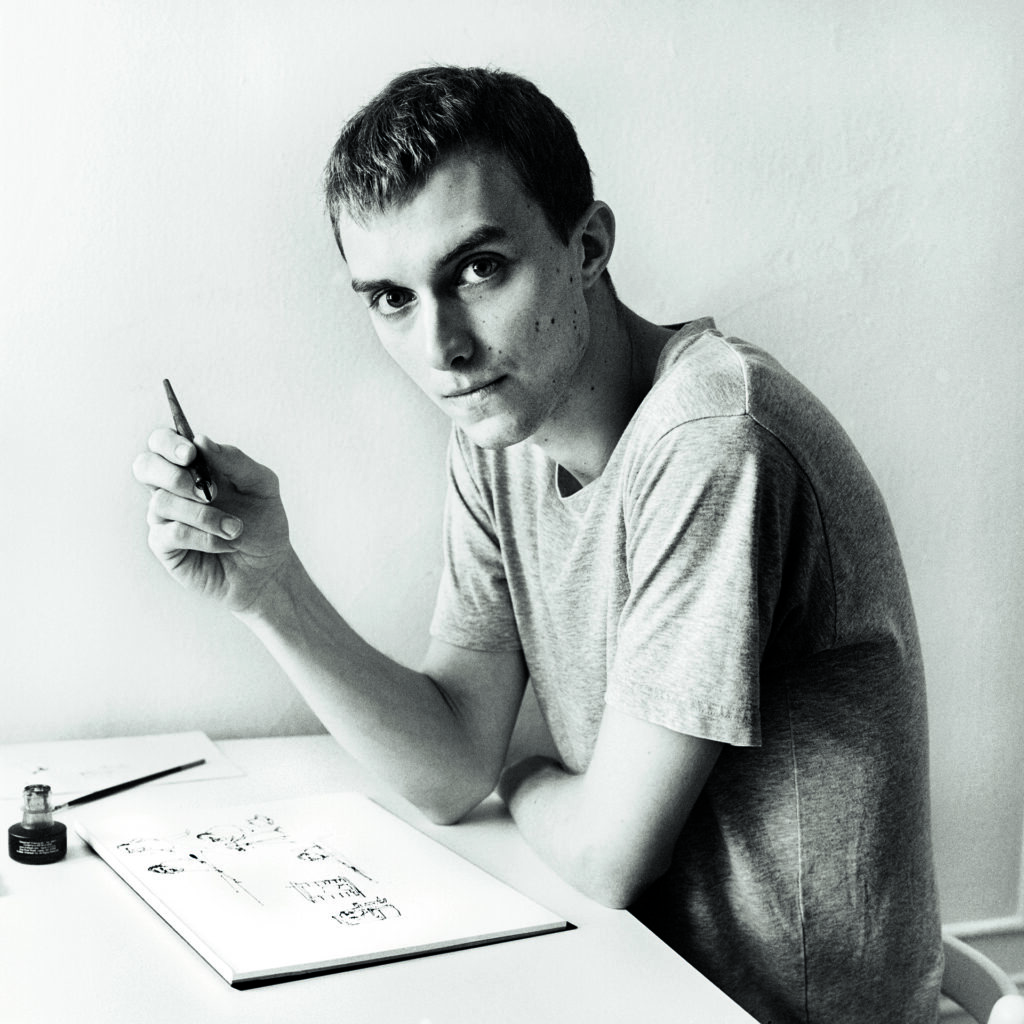

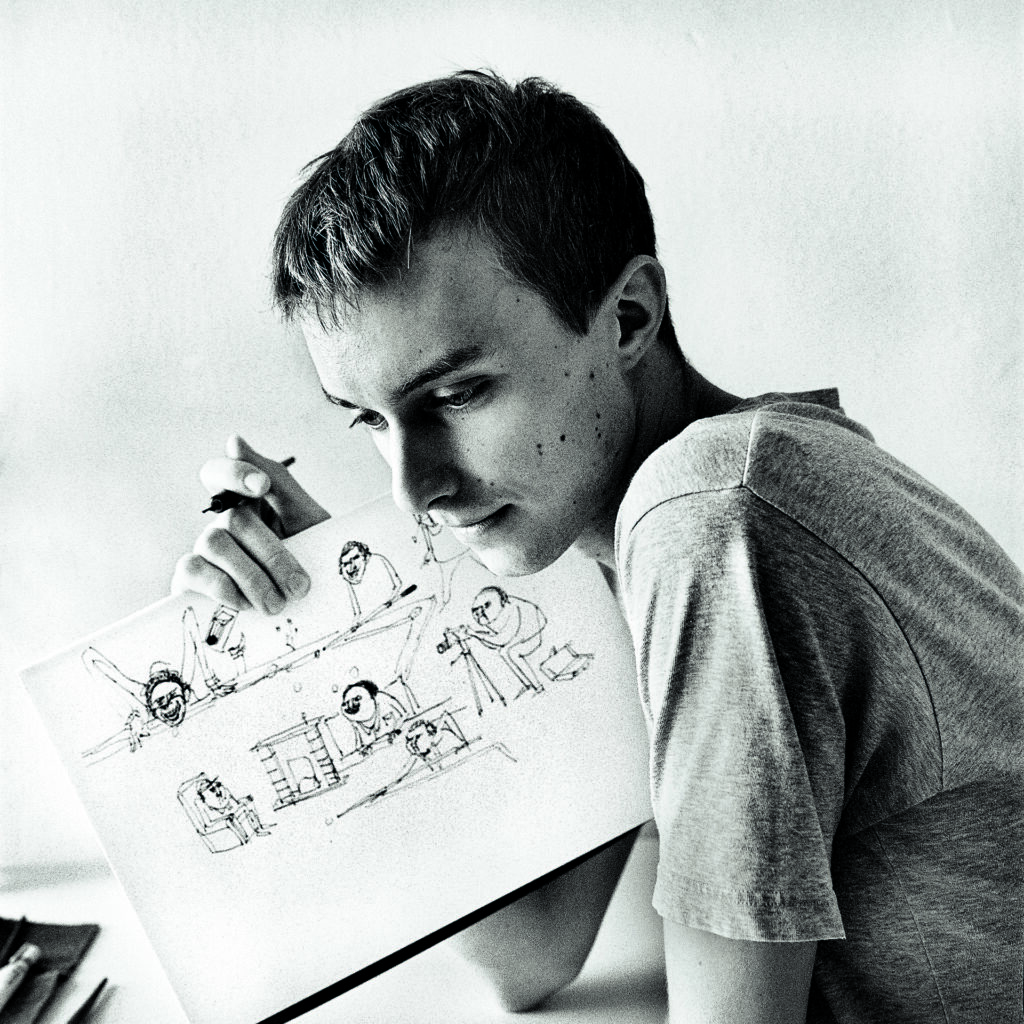

In a now grand tradition, the magazine’s cartoonists identify themselves as “New Yorker Cartoonists”—but in truth they work for themselves. They remain, for the most part, solo acts, seeing what most of us see, then running that through their brain’s highly attuned and complex cartoonist gadgetry. They’re hard workers, these cartoonists—they always have been. As you will see in Alen MacWeeney’s photographs of the artists in At Wit’s End: Cartoonists of the New Yorker, they are a determined lot.

*

Photo by Alen MacWeeney.

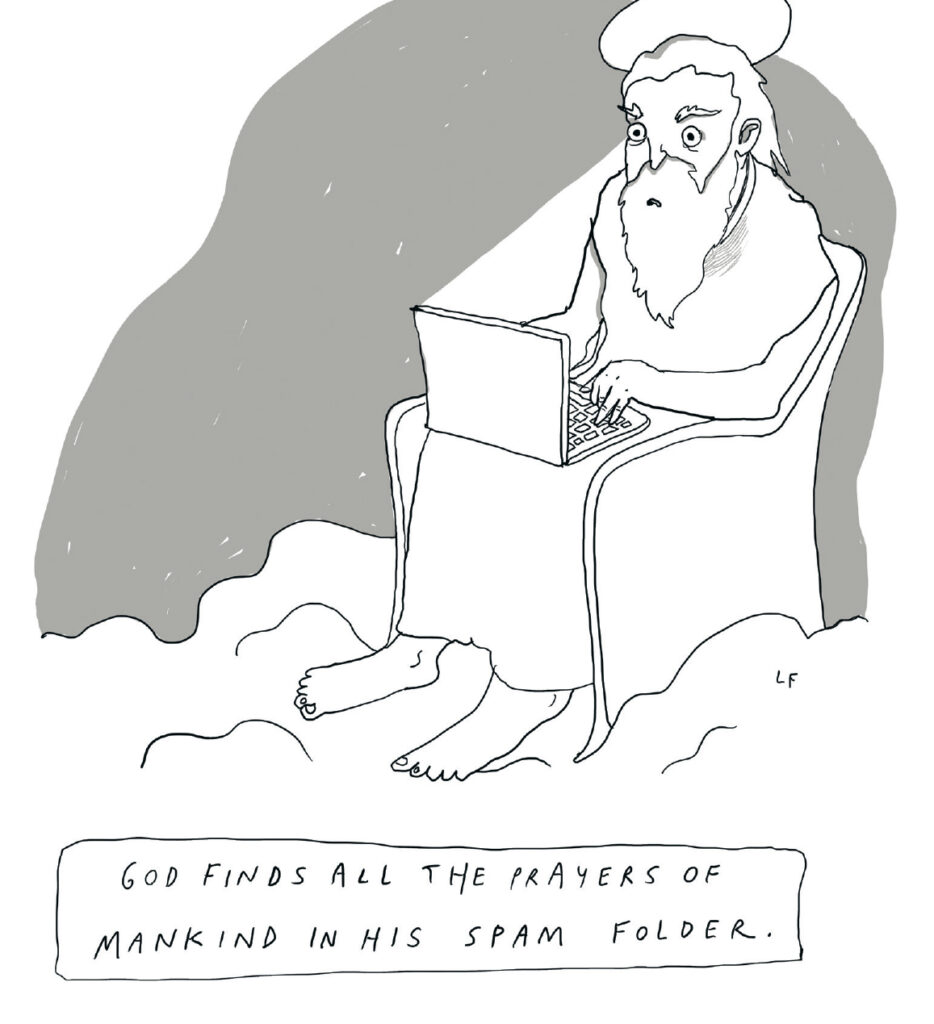

Liana Finck

Liana Finck stole the show. In the best moment of the 2015 documentary Very Semi-Serious: A Partially Thorough Portrait of “New Yorker” Cartoonists, the camera lingers over her nervous appearance in the cartoon department (“My voice is wobbly”)—we see the novice allowing the world into her world. “I’ve been doing these constantly since I was sixteen…but I never bring them in because I self-censor. I’m getting more confident about being able to take rejection.”

Work-wise, and perhaps worlds-wise, there are at least two Liana Fincks: the Instagram Liana and the New Yorker Liana.

On Instagram, her work appears steadily throughout the day as stream-of-consciousness missives, sometimes drawn as simply as a circle face with dots for eyes, a line for a mouth, perhaps a hint of a stick-figure body.

Her New Yorker work, appearing every few weeks, conforms to some of what might be considered conventional cartoon boundaries: a drawing, playing off a theme, usually with a caption, delivering the time-honored one-two cartoon punch (although punch may be too aggressive a word). She told one interviewer that she thinks of her style as “very messy, very quick.” Messy and quick works well for her—an appealing mix that reminds one of the late Dean Vietor’s work. His drawings always looked as if they were in motion, about to unravel.

Liana’s drawings are delicate, but we don’t fear for their future stability.

If there was a family tree of illustrators and cartoonists, her lines seem to be an offshoot of the illustrator Brian Rea. The words and ideas are another thing altogether; Mr. Rea, as an illustrator, works off texts, while Liana provides her own.

In her numerous public appearances in the past few years since her debut at The New Yorker, what comes through when she speaks is often what sounds like an unedited New Yorker cartoon caption. She catches the audience by surprise. The audience howls.

*

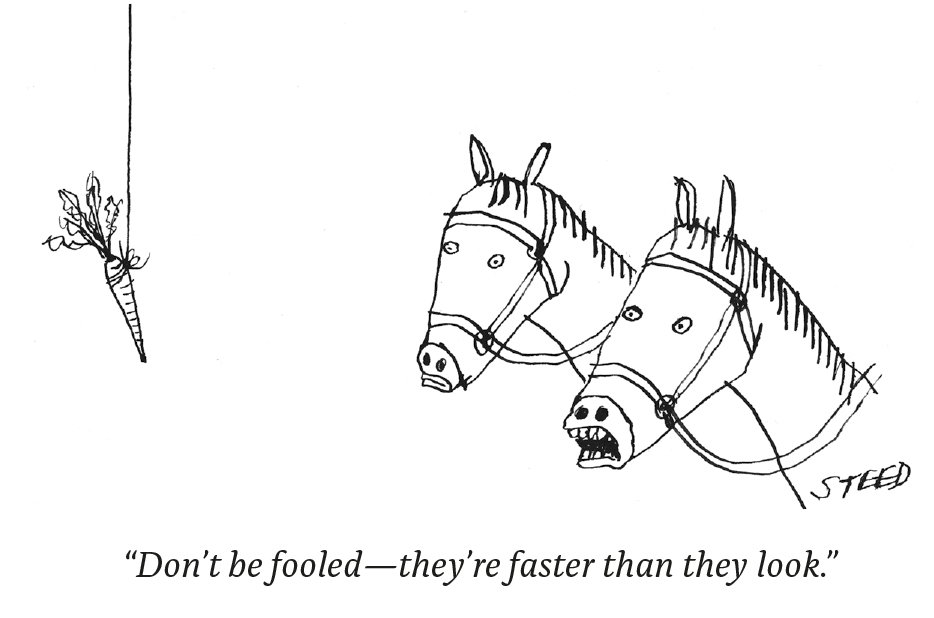

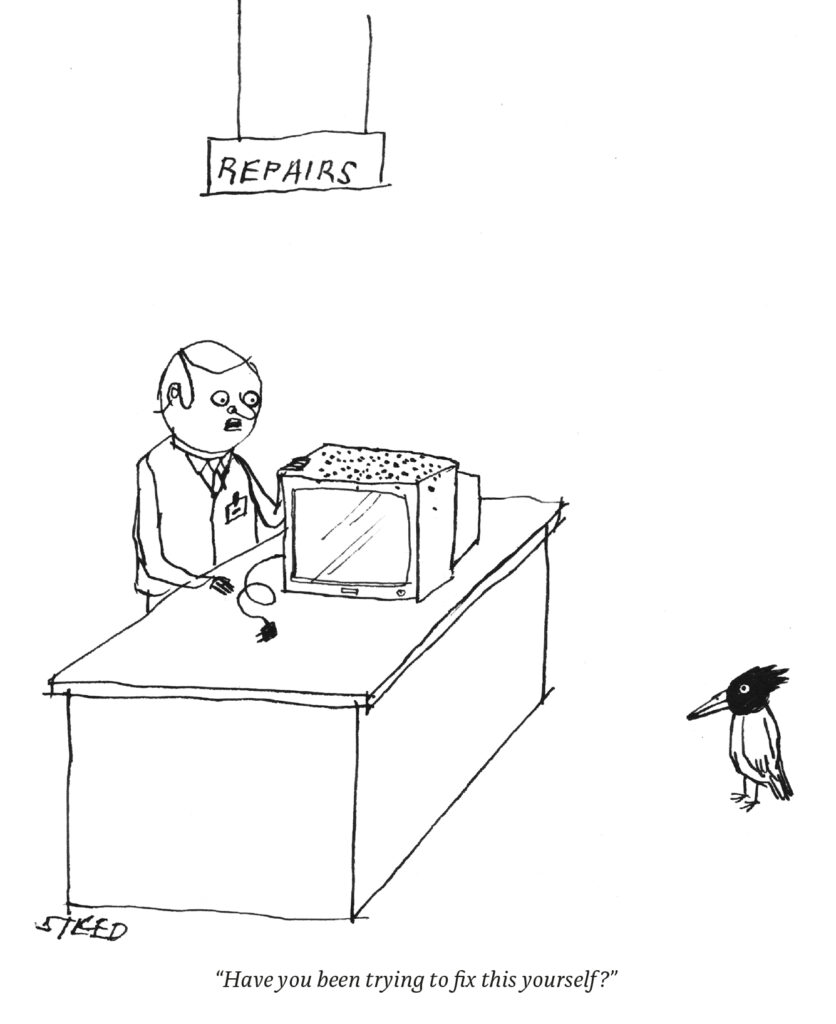

Ed Steed

There’s a lot of blatant Sturm und Drang in Ed Steed’s work; there’s a fair amount of bloodletting too. You don’t expect that, or maybe you wouldn’t expect it if you’d met him.

His “journey” to The New Yorker was perhaps not unusual—being that he’s English, it just took more miles than most to get there. In 2014, less than a year after he began his New Yorker run, he told me how he came to the magazine:

“I discovered New Yorker cartoons recently, just a couple of years ago. I saw them online and decided I would like to do that too. I hadn’t been interested in cartoons since I’d outgrown the stuff I looked at when I was young, but these were clearly different. I started writing down ideas straightaway. When I had a bunch of what I thought were good ones I sent them in.”

The “good ones” are humorous night-lights glowing in a darkened hallway. He takes on, like all his colleagues, the desert island, the sidewalk robbery, the police lineup, superheroes—but he isn’t satisfied with the standard scenario and a good caption; he’s brought some measure of uneasiness to the page.

All cartoonists offer up a stew incorporating shifting ingredients. Steed’s contains teaspoons of Ralph Steadman (without the splashes of ink), Edward Gorey, Gahan Wilson, and Charles Addams. In other words: work that doesn’t lightly amuse.

And then there are the occasional freewheeling graphic essays appearing on the New Yorker’s website. In one, he visits Chairman Mao’s tomb in Beijing. Not able to draw on-site, he memorizes while visiting, then, later, commits to paper what he remembers. He returns again and again to see Mao and memorize until he’s filled in the details. It’s like a short silent movie.

Steed’s people—his cast of characters—are cramped folk. It might take a lot of looking to find one with a neck. Their circular heads sit tight to their shoulders. Their faces feature scrunched eyebrows, grimacing mouths, and scritchy-scratchy hair. These people seem perfectly content in the world Ed’s created for them.

__________________________________

Excerpted from At Wit’s End: Cartoonists of the New Yorker. Copyright © 2024. Photographs by Alen MacWeeney and profiles and introduction by Michael Maslin. Cartoons by Liana Finck and Ed Steed. Published by Clarkson Potter.