TELLURIDE, Colorado — “I’m the last of the Mohicans,” ruminates David Cassirer from the dining room of his modest frontier-style house in the mountains. David is the last surviving heir of the Nazi-looted Camille Pissarro painting “Rue Saint-Honoré, après midi, effet de Pluie” (1897), the subject of a serpentine legal case that has wound up and down the American court system for the last 25 years. In the decades since his family discovered the painting in the possession of the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid, Spain, David’s father, mother, and sister have all passed away. David has no children.

In late March, I drove four hours through the raw, untouched New Mexico and Colorado landscape to meet David at his home near Telluride.

“It’s my style to get away from it all,” he said, gesturing to the lakes and mountains visible from a window. While most of the house has the feel of any standard American abode, heirloom objects from his family’s past dot every room. “Having these things around connects me spiritually, a little bit, to Lily,” David says, referring to his grandmother, Lily Cassirer.

Lily’s leather steamship trunk, a reminder of her escape from Nazi-occupied Europe to the United States, sits below a bedroom window. An imposing hand-carved wood China cabinet is in the living room, a piece of furniture in which David and his sister used to get into trouble for hiding inside. There’s also a 16th-century chest, a turned wooden lamp, and a Phillip Harth bronze sculpture of a walking leopard.

David is a former jazz pianist, arranger, and conductor. He was something of a musical prodigy while growing up in Cleveland and left home as a teenager to study music in Boston. He was a member of a popular jazz trio, performed regularly on television, and entertained America’s elite. However, his father Claude Cassirer, a Holocaust survivor and the heir of the illustrious publishing house and art gallery Kunst and Künstler in Berlin, never approved.

“My father went to his grave at almost 90 years old, believing that the whole idea of pursuing [piano] was to avoid work. I was a big disappointment,” he said.

Towards the end of his father’s life, however, the two men bonded in their mutual fight for the Pissarro painting.

David knows exactly what he will do with the proceeds from the sale of the painting, estimated at $60 million, if it ever comes to fruition. Although a sizable portion of the funds would go to repaying the legal fees for the case, he wants to establish a nonprofit to assist others in recovering their Holocaust looted artwork — a foundation David describes as “my father’s mission.” Claude wanted the funds “available to other people that are similarly situated, so they won’t have to go through 25 years of what we did,” David explained.

On multiple occasions in the last quarter century, the case seemed dead in the water. But like Lazarus, it has risen yet again. Advocacy efforts have led to new laws at the state and federal levels.

“One of the ways we’ve helped,” said David, “is to do things like persuade people … My father would be proud of the various precedents that this case has set, that others are able to cite it in their own cases.”

In March, the United States Supreme Court remanded the case back to California’s 9th Circuit Court of Appeals — the second time America’s highest court has done so — asking it to reconsider the case within the framework of California’s recent Assembly Bill (AB) 2867. Formulated specifically in response to the shocking twists and turns of the Cassirers’ multi-decade quest to recover the Pissarro, AB 2867 widened the scope and timeframe of recovery claims on artwork and personal property lost due to persecution, whether in the Holocaust or otherwise. It was signed into effect by Governor Gavin Newsom in September 2024.

Now, in a significant win for David and his team, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the case back to US District Judge John Walter on April 30 for a new ruling.

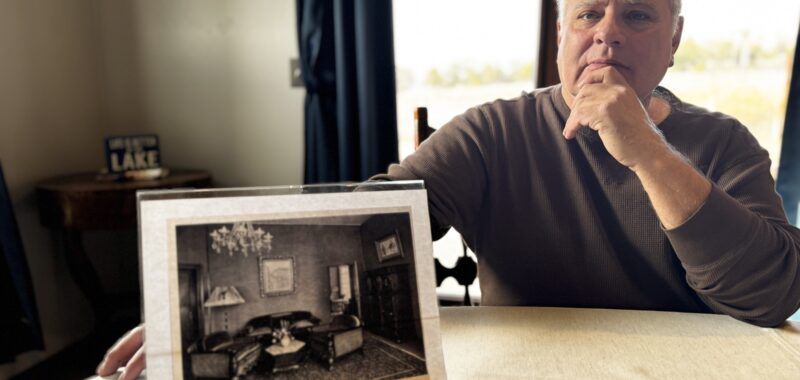

Although David and his family once believed they had two smoking guns — an insurance photograph showing “Rue Saint-Honoré” hanging proudly over the velvet sofa in the parlor of their Berlin apartment and the remnants of a label on the back of the painting that shows the partial name and address of their family’s gallery, they were not enough to restitute the painting.

Restitution cases are often less about the painting and the merits of the case, than about legal statutes, the lack thereof, or in this case, something known as “choice of law,” whether a foreign sovereign nation can be sued in US Courts. During a 2022 Supreme Court hearing, which led to the unanimous 9-0 decision to remand the case back to the 9th Circuit for the first time, Justice Stephen Breyer mustered a joke about one hour in: “Can everyone agree that this is a beautiful painting?”

The Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum has also been particularly keen on retaining ownership of the artwork, despite the seismic shifts that have taken place both in art restitution practice and the moral implications of holding onto Nazi looted art. A new exhibition at the museum, Proust and the Artists, which opened in March 2025, features “Rue Saint-Honoré” as the main marketing image, enlarged nearly floor-to-ceiling size at the front of the show. One of the Cassirers’ lawyers, Sam Dubbin, called it “a deeply misguided attempt by the museum to assert ownership over the painting” in a recent email.

“It is also an outrageous display of arrogance and tone deafness – using not only stolen art, but a masterpiece of French Impressionism looted by the Nazis from a Jewish family,” Dubbin told me. “Highlighting the painting in the exhibit shows just how important it is, and further demonstrates why Spain should return the painting to the Cassirer family instead of flaunting its possession which is derived from Nazi atrocities.”

It’s hard to underestimate the prominence of the Cassirer family in Berlin before World War II. “My father was raised like the Kennedys or the Rockefellers,” David said, “beyond wealthy.” The original fortune was made in coal mining and steel production, enabling the subsequent generation to become cultural patrons. Kunst and Künstler shepherded the avant-garde and modern art movement in Germany.

Although the Cassirers were well assimilated into German society, they sensed the Nazi threat early on and made plans to leave the country. “They were trying to get ahead of Hitler,” David explains, “when no one knew this would get that big.”

The Cassirers fled in 1939, only after being forced to pay the “escape tax” levied on Jewish refugees. For the family, it amounted to the equivalent of $4 million today, and required handing over some of their prized possessions, including Lily Cassirer’s favorite work of art: “Rue Saint-Honoré.”

They were the lucky ones. David’s great aunt, who stayed behind to take care of her elderly mother, would perish along with her family in Auschwitz. The Nazis traded “Rue Saint-Honoré” to another Jewish family for Old Master paintings of Hitler’s liking. That family fled to Holland with the painting, not knowing that Hitler was right behind them. “Then the Nazis took it again,” David says.

In boarding school in England, David’s father Claude was distanced from what was unfolding in Germany. While on holiday in the south of France with a British classmate, the Vichy government began carefully inspecting passports on exit and prevented Claude from returning to England. “He had a Nazi passport and they wouldn’t let him out, so they sent him to a terrible detention camp in Morocco near Casablanca with no running water and no toilets,” David recounts. He contracted typhoid fever and nearly died, dropping to only a hundred pounds.

In 1941, the camp was liberated by the Allies and Claude was sent on a ship to America, where he was quarantined on arrival in New York City. He was released into a brave new world, a new continent with no family and no connections.

“He walks out broke, without a job, and had to start all over,” David recounted. “But he was just the right guy — immigrant and young enough to still be tough.” He snagged a job as a photographer’s assistant and ended up in Cleveland, Ohio, where there was a robust Jewish community.

Claude became a successful photographer, documenting the likes of Paul Newman, Eleanor Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. His mantra was “it’s more important to click with the people than the pictures.” During the war, he met his future wife, Beverly, a descendant of Russian Jewish immigrants, on the train between Cleveland and New York City. “She was just swept off her feet,” David describes.

In December 1999, the telephone rang at the Cassirer residence in San Diego, where the couple had retired. A friend had just spotted “Rue Saint-Honoré” inside a book accompanying an exhibition of Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza’s extensive art collection, triggering the family’s multi-decade legal battle.

When I asked about what his father would think of how far they’ve come with this painting, David responded, “Like most Holocaust survivors, they were very modest. They were humbled by what happened, where Hitler had such a terrible impact on the world.”

“So they were far more modest than they were in their heyday, and they would be stunned at the interest in this case, at the amazing amount of public support, not just from Jewish people, but from everybody,” David continued. “But my father would be more pleased when we finally make a recovery, and we can get this art returned.”

For David, this case is more important than the painting itself, its potential sale, or the foundation he hopes to create. It’s ultimately about the stories of those who lived through fascism and genocide, and about giving a voice to the voiceless who were unable to share what happened to them.

“This is a different angle on the Holocaust, rather than the harsher angle of the people, Jews and others, in concentration camps or death camps,” David said with conviction, standing next to a reproduction of “Rue Saint-Honoré” that hangs in his living room. “That is a little easier to take, because we’re staring at this beautiful art and telling the story of how it was taken from these people, from its real owners.”