[ad_1]

This one’s personal. Dylan Thomas bestrides modern Welsh poetry like a chubby-cheeked, shabby-blazered colossus. Any Welsh poet who tries to be modern therefore has to pass through him first, whether they want to or not—myself included. It’s hard even to get off first name terms with him, so I’m afraid that’s what we’re going to be stuck with here. Dylan made the weather, and now the rest of us can choose either to get drenched in it, bring an umbrella or head somewhere else altogether.

Article continues after advertisement

Fifty years ago the critic Harold Bloom put forward a famous theory, “The Anxiety of Influence.” Bloom’s basic idea was that poets since the Enlightenment have always been writing in the shadow of their forebears—Homer, Dante, Shakespeare. The best, or ‘strongest,’ modern poets turn that inferiority complex into an asset. They take the lead in a dynamic confrontation that produces fresh new work. But however successful they might be in that struggle, the writing process remains fraught with angst:

For the poet is condemned to learn his profoundest yearnings through an awareness of other selves. The poem is within him, yet he experiences the shame and splendor of being found by poems—great poems—outside him.

Dylan Thomas is that titanic other, rambling in the background of Welsh literature. Reading him down the years, I’ve been ‘found’ by all manner of familiar insights and strange music relating to my country, a place Dylan memorably called “the loud hill of Wales.” Often now, when I pick up a pen or sit down at my laptop, I see his nonchalant, slightly dumbstruck face staring back at me. There he is, propped up on an elbow in the grass, tie bunched haphazardly under his cardigan. There he is, supping a pint in the corner of a Fitzrovia pub, playing up to his role as court bard—or court jester—of the bohemian London scene.

In several of his greatest poems, Dylan makes the avant-garde sexy and immersive like no one else.

Or here he is, in a 1950 letter to the American poet John F. Nims and his wife, conjuring a better, more colorful self-portrait than anything I could come up with:

Remember me? Round, red, robustly raddled, a bulging Apple among poets, hard as nails made of cream cheese, gap-toothed, balding, noisome, a great collector of dust and a magnet for moths, mad for beer, frightened of priests, women, Chicago, writers, distance, time, children, geese, death, in love, frightened of love, liable to drip.

I’ll go out on a limb and say there’s never been a funnier citizen of the Republic of Verse than Dylan. This bravura list contains many of his characteristic comic tics: riddling sound play, riffs on slang and proverbial phrases, semantic switcheroos. On its own, “hard as nails” would be a sarcastic quip, but throw in “made of cream cheese” and the cliché opens onto complexity. Maybe this is a person who presents one way—tough, bristling, imperturbable—to cover up the fact that he’s really nothing like it. Get too close and he could turn to a squidgy mess in your hands. His public image is “liable to drip.”

Other true words are spoken in jest. There’s the withering snapshot of the poet’s prematurely aging body, hammed up for effect, but only in the way a good cartoonist will exaggerate their subject’s features to nail a likeness. By this point in life—he was 36—Dylan’s youthful, floppy-haired charm had started to coarsen along with the blood vessels in his nose. He was growing in international fame as a writer, broadcaster and speaker, but acquiring just as big a reputation as a bon viveur. Ask anyone who knew him a little, and they’d likely tell you he was the life and soul of the party, “mad for beer,” and not to be counted on if you lent him a tenner. Those who knew him better might point to his sporadic fits of generosity, his deceptively industrious working habits, or the shyness that afflicted him between bouts of drink-fueled bravado—but they were just as likely to be stood up by him or left out of pocket.

It’s a good job, then, that his words were beautiful. The opening stanza of “Fern Hill” is as good an advert as any for the joys of reading Dylan at his best:

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honoured among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daisies and barley

Down the rivers of the windfall light.

“Fern Hill” commemorates the Carmarthenshire farm where Dylan spent childhood summers, 30 miles away from Swansea, his industrial hometown. The poem was written deep into the Second World War and comes saturated in rose-tinted technicolor. The real farm had been rough as old boots—in a rather more realistic story, Dylan wrote that it “smelt of rotten wood and damp and animals”—but here it blossoms into an al fresco paradise. I can think of no work that better captures the great delusion of entitlement that a happy childhood brings: how the loved and carefree boy becomes a “prince of the apple towns,” romping around his domain. You don’t have to have grown up near a farm with 15 acres and an orchard to know how that feels.

The sound of the thing is as important as its meaning. In fact, you could argue that sound is as integral to meaning as the definition of any particular word or phrase. The poem’s rhythms skip and tumble where others plod. There’s an abundance of muted syllables, giving everything a gamboling, lamb-like gait. (“Happy as the grass was green” is an example of what I mean: you’d only really stress ‘happy’, ‘grass’ and ‘green’, so the other four syllables rush along, excitedly filling the gaps.) No single line is quite the same, rhythmically, as any other.

At the same time, set beside these subtle variations, Dylan assembles a rigid design scheme. Each of the poem’s six nine-line stanzas conforms to a pattern of syllables per line. (The pattern, if you want to count, goes 14, 14, 9, 6, 9, 14, 14, 7, 9 in stanzas one, two and six, and 14, 14, 9, 6, 9, 14, 14, 9, 6 in stanzas three, four and five.) In effect, this arrangement blows a raspberry at the great poetic tradition he’s inherited. If we think of the history of English verse as, essentially, the history of iambic pentameter—the ten-syllable, ti-tum-ti-tum-ti-tum meter that we’ve met in Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton and Wordsworth—then this is a gorgeous way of doing anything but iambic pentameter. The 14-syllable lines expand lushly beyond that mark. The six- and seven-syllable lines fall laughingly short. The nine-syllable lines, on the other hand, flirt with iambic pentameter while always just eluding it—the lopped-off extra syllable quite literally knocks that meter off its feet.

I see all this as a form of Welsh jazz. “Fern Hill” has the same combination of technical wizardry and offhand swagger that defines the music of Duke Ellington and John Coltrane. A set structure provides a road map, allowing the artist to vary their theme while never straying far from home. On top of rhythm there are the individual notes that form the melody, and Dylan pays just as much attention at this level. Throughout the poem, vowel calls out to vowel—’boughs’ to ‘towns’, ‘barley’ to ‘starry’—in a riotous sonic display. (The poetic term for these meshing vowels is assonance.) Key words repeat from stanza to stanza, such as ‘green’ and ‘time’, which fuse at the end in the magnificent phrase “Time held me green and dying.” Given such virtuosity, it comes as no surprise to learn that Thomas bashed through some 200 drafts of the poem, fine-tuning a work he knew was shaping up to be his masterpiece.

*

First published in the literary magazine Horizon, “Fern Hill” reached a wider audience when it appeared in Dylan’s postwar volume, Deaths and Entrances (1946). Almost immediately, readers latched on to it as an elegy to childhood innocence, delivered amid the rubble and ash. His attunement to the public mood had been hard-won. After failing an army medical in 1940, he entered into a type of wartime service writing propaganda scripts for the Ministry of Information. First in London and then in Swansea, he witnessed the ravages of the Blitz first hand, and several of his poems from the time pay tribute to life and death on the Home Front. The most ambiguous and beautiful of these is “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London.” Rejecting any easy consolation, the speaker vows not to “blaspheme down the stations of the breath / With any further / Elegy of innocence and youth.”

Perhaps the most significant development of Dylan’s war years came with another type of service he was able to offer. Starting in 1937, but ramping up in the early ’40s, he became a regular presence on BBC radio stations. He chipped in for the Beeb with lectures on a variety of literary and autobiographical themes, from “Life and the Modern Poet” to “Persian Oil.” The 1940s were “the great age of radio,” according to William Christie, and Dylan “would become one of the kings of the virtual castle.” Apart from being a vital outlet for reliable information during wartime, the BBC provided continuity in the intellectual life of the nation. As with the cinema boom of the early twentieth century, writers were given more or less free rein to invent a new medium for a mass audience, and Dylan’s talents rose to the occasion. In his hands, the wireless flowered into a glorious playground for language—a place to be demotic, offbeat and lyrical, all without leaving the listener behind.

This happy relationship would eventually result in Under Milk Wood, quite probably the most original radio drama of all time, and the zenith of Dylan’s writing about Wales. Once heard, the goings-on in Llareggub—a fictional Welsh everytown, whose name was conjured from ‘Bugger all’ spelled backwards—are impossible to forget. As is Dylan’s uncanny manipulation of intimacy over the airwaves:

Come closer now.

Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets in the slow deep salt and silent black, bandaged night. Only you can see, in the blinded bedrooms, the combs and petticoats over the chairs, the jugs and basins, the glasses of teeth, Thou Shalt Not on the wall, and the yellowing dickybird-watching pictures of the dead. Only you can hear and see, behind the eyes of the sleepers, the movements and countries and mazes and colours and dismays and rainbows and tunes and wishes and flight and fall and despairs and big seas of their dreams.

From where you are, you can hear their dreams.

On the page, a phrase like “slow deep salt and silent black, bandaged night” looks ungainly, a ridiculous mouthful; on the radio, the warp and weft of those six strung-out adjectives is magical. Here and in several of his greatest poems, Dylan makes the avant-garde sexy and immersive like no one else.

Before he got to Llareggub, however, he earned his stripes as a chronicler of his real-life home patch. Swansea emerged as the main subject of no fewer than four radio talks, a number that increases if you include his wider west-Wales hinterland of the Gower, Carmarthenshire and the Aeron Valley. Of these homeward-looking broadcasts, “Reminiscences of Childhood” has justifiably become the most famous, mainly for the following sentence:

I was born in a large Welsh industrial town at the beginning of the Great War: an ugly, lovely town (or so it was, and is, to me), crawling, sprawling, slummed, unplanned, jerry-villa’d, and smug-suburbed by the side of a long and splendid-curving shore where truant boys and sandfield boys and old anonymous men, in the tatters and hangovers of a hundred charity suits, beachcombed, idled, and paddled, watched the dock-bound boats, threw stones into the sea for the barking, outcast dogs, and, on Saturday summer afternoons, listened to the militant music of salvation and hell-fire preached from a soap-box.

What a panorama, what a sound. “Ugly, lovely town” is the hero phrase, a reverse-pride motto that nowadays you’ll find blazoned across Swansea landmarks. At a literal level, it captures the grit and beauty of the place, but more than that it’s a genius piece of sound play. Trust Dylan to tap into the hidden connection between two apparently opposite words. The identical vowel sounds nudge us into an important realization. So often in Wales, ugliness and loveliness go hand in hand; slag-heap grays are smeared against rolling greens and “splendid-curving shore[s].” This is assonance lifted to the level of social commentary, proving once and for all that the music of language didn’t just decorate Dylan’s verse—it structured the very contours of his thought.

*

As with all good anxieties of influence, my feelings about Dylan are decidedly mixed. A surprising amount of his poetry leaves me lukewarm or cold. Endlessly pyrotechnic and thick with symbols, it can quickly become dry and airless. Recurring motifs of life and death—wombs, worms, milk, hearts, graves, grass—vibrate with the relentless energy of a fridge. The intensity of his music overheats: not so much the syncopation and swing of jazz, as the grinding groove of industrial techno. Take “Altarwise by Owl-Light”:

Death is all metaphors, shape in one history;

The child that sucketh long is shooting up,

The planet-ducted pelican of circles

Weans on an artery the gender’s strip […]

And so it continues, each line surging further and further into the red, across ten sonnet-length sections. Dylan understands the risks of his chosen style. “Death is all metaphors” keys us into the abstract nature of the poem—how each apparently concrete noun stands for something bigger than itself—but it doesn’t make the end result less risky or hard to fathom. (If anyone can shed light on “planet-ducted pelican of circles,” send answers on a postcard to the usual address.) Risks can be wonderful when they pay off, but I’m not sure Dylan’s always do.

The story of Dylan is a story of big talent, scurrilous gossip, silliness, grift, technological and social change, and excellence thriving quietly in plain sight.

These feelings are embarrassing to me because they lump me in with a long line of snobs and philistines. As John Goodby points out, “Thomas was resented by many during his lifetime for his combination of stylistic exuberance, roaring boy reputation and common touch.’ For an example of this condescension, Goodby points to George Steiner’s characterization of him as “an ‘impostor’ peddling bardic excess ‘with the flair of a showman to a wide, largely unqualified audience [which] could be flattered by being given access to a poetry of seeming depth’” “Unqualified audience” is a particularly noxious insult. Dylan was a grammar-school boy whose diverse tastes and flair as a writer were largely self-taught. What’s more he was Welsh—a double novelty—and his poetry seemed to answer an appetite for something primitive and mystic in the interwar mood. The fact that it was scrupulously measured, and influenced by everything from Freud to French Symbolism to Thomas Hardy, hardly counted. Dylan became everybody’s favorite noble savage, until the tides of taste moved on and he found himself an “impostor.”

The mercy was that this didn’t happen, fully, until after his death. The death part came prematurely, in 1953, and its circumstances have been ramped up into rock ’n’ roll legend. What we know for certain is that it happened in New York City, at the tail end of one of several American speaking tours that he embarked on for money and adventure from 1950. He claimed to hate America and to miss his wife and children terribly whenever he was away from them. But if he travelled to the States against his will, then he did a good job of fooling the acolytes, girlfriends and barflies he palled around with while he was there. He tore into the boozy East Coast literary circuit with nervous relish, blotting out money worries, marital strife, and unresolved grief over his father’s death in 1952.

The most tenacious aspect of the Dylan death myth concerns his final words. On Sunday November 8, he had a big drinking session at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village. (The bar’s still there today, doing a brisk trade on Dylan’s name.) After being rushed to the emergency room of St. Vincent’s hospital in the early hours of Monday morning, he’s supposed to have said,

“I’ve had eighteen straight whiskies—I think that’s a record!” before giving up the ghost. (In some versions of the story, he’s receiving a scrub bath at the time of death, watched over by the poet John Berryman.) As his granddaughter Hannah Ellis argues, it’s “highly likely that he did” speak these words, yet “very doubtful” that the alcoholic numbers would have added up like that. (People who have done their homework place the whisky tally more in the region of six to eight.) On a cursory inspection of Dylan’s medical notes, it becomes clear that he was a very unwell man by the autumn of 1953, battling a host of undiagnosed respiratory problems. The drinking made matters worse, but didn’t poison him to death.

No matter: the boozehound story quickly elbowed out any complicating factors. Dylan rose phoenix-like from his ashes to become the poster boy for a generation of beatniks, dropouts and moody students. The American poet Kenneth Rexroth summed up his allure when he eulogized Dylan alongside another tragic genius who blew himself out in the mid-1950s. “Like the Pillars of Hercules,” Rexroth wrote, “like two ruined Titans guarding the entrance to one of Dante’s Circles, stand two great dead juvenile delinquents—the heroes of the post-war generation: The saxophonist Charlie Parker, and Dylan Thomas.” Parker was a visionary and uncompromising musical stylist who pioneered the experimental postwar jazz style known as bebop. A heroin user, he was also a drug addict on a different scale from Dylan. The comparison domesticates Parker’s rage and alienation—much of which came down to racial prejudice—while burnishing Dylan with a wild-boy reputation he only half deserves.

This questionable legacy has proved, paradoxically, to be the guarantee of Dylan’s ongoing celebrity. To this day he remains one of the few genuinely box-office poets, forever in print and depicted on screen and stage by a parade of actors including Alec Guinness, Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Rhys. Meanwhile, in Poetry Land, his stature as a serious writer has pretty much collapsed. His verse sounds overly rich and pretentious next to the stripped-back social realism that ruled the roost in British poetry for many years. In Goodby’s words, “Thomas is a kind of embarrassment on just about every level of the mainstream poetry world. His work is powerful and won’t fade away, and it appears that something needs to be said about it; but, for some reason, it cannot be made to fit the standard narratives and so nothing gets done.” That situation may be changing, but Dylan’s wayward reputation and mythic death remain obstacles to any proper appreciation of his writing.

My own burdens of anxiety are connected to all this. I said that a Welsh poet trying to be modern has to pass through him, and I think that’s true. Dylan still represents the pinnacle of a certain type of Celtic noise. Mellifluous, muscular, turbo-charged by scripture and fireside banter, it’s an incredible sound. I tune in to his music from time to time and find it hard to escape. (If this chapter were about me or my poetry, I’d list examples.) To push that music further would result in chaos; to backtrack, as many Welsh poets did in the decades following his death, too often leads to a music-free dead zone on the outskirts of prose. A happy medium is hard to find.

Why should this national psychodrama be of interest to anyone outside Wales? Maybe it isn’t, but I flatter myself to think that it might be. The story of Dylan is a story of big talent, scurrilous gossip, silliness, grift, technological and social change, and excellence thriving quietly in plain sight while the rest of the world goes doolally for a myth. It tells us a lot about celebrity culture and the shifting sands of cultural taste. None of this means anything, of course, next to the glow of recognition I get from walking the Welsh coastline and turning to salute the “heron / Priested shore” (“Poem In October”). The shore was there long before Dylan named it that—but Dylan gave me the words to call it my own.

__________________________________

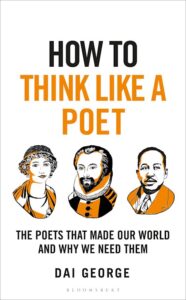

Excerpted from How to Think Like a Poet: The Poets That Made Our World and Why We Need Them by Dai George. Published with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © Dai George, 2024.

[ad_2]

Source link